Making Room in My Triangle

Working in the kitchen with others is like a dance. For years, my husband and I were out of step—more mosh pit than ballet. Then we went to Sicily.

This Thanksgiving marks five years since the Great Fowl Folly—a kitchen disaster so legendary, it permanently banished my husband from holiday meal prep.

Let me backtrack. As a kid, whenever Mom was in the kitchen, I was glued atop the rickety, metal step stool. When she made cookies, I watched her cream softened butter and sugar with her hand-held electric beater. I’d crack eggs into the mixture and watch them slip into the spinning heads, creating a silky batter. One of the beaters would be mine to “clean” – this of course, was before we worried about the dangers of uncooked eggs.

Fast forward, to when I had my kids. Two boys, Alex and James. Because I worked all day, I included the boys in our meal prep - to maximize time together. My little sous chefs were tasked with fetching ingredients from the cupboard, pouring in liquid, stirring, and deciding what spices to put in a marinade. By four, James had his own special marinade. When they were in high school, we subscribed to meal prep service, Blue Apron. And their comfort in the kitchen soared.

James took a two-week cooking course one summer, and Alex, not to be outdone, was studying cooking techniques on YouTube. I was at work when they created a brown sugar rub for salmon and grilled it on a cedar plank. Unfortunately, they hadn’t soaked the plank enough and it burst into flames. They howled with laughter telling the story of them running around a wood deck with Salmon Flambé. Notably, the salmon was cooked to perfection under the never-to-be-repeated brûlée.

If Tim and the boys were comfortable in the backyard throwing a baseball and football tackling, the boys and I performed in the kitchen like a choreographed ballet. Hot pots and people maneuvered around each other, knives flourished, spices were nabbed from the cabinet. No bumps or bruises.

It wasn’t like that with Tim. He never cooked for himself aside from toast or oatmeal, and never showed any interest in cooking. But he was terrific at cleaning up. Maybe it was because all of us were convening in the kitchen or maybe he felt guilty sitting while we worked, but he would jump up and rush to the sink to wash dishes.

I wish I could tell you it was a good thing. But at 6’4 and 200 pounds, he has a wing span like a pterodactyl. And if the boys and I are like a ballet, Tim and I are navigating a mosh pit. If he spies something on the other side of my 5’2 frame, he lunges for it. It’s like a ship’s boom in my kitchen that I have to duck to avoid.

“What are you doing?” I say with more than a trace of irritation.

“I’m just doing dishes,” he says, equally annoyed.

“Get out of my triangle,” I yell. I may have menaced him with a sharp object. Not one of my more graceful moments.

In any event, it became a family joke. Stay out of Mom’s triangle.

It’s November 2019, and Alex and James insist they are making the Thanksgiving meal. Fortified with a recipe from some designer chef, Alex sent me the shopping list. I think it was 422 vegetables, a garden of fresh herbs for a bouquet, turkey shears, and a bag of kosher salt. He would spatchcock the turkey.

They arrived on Wednesday around 9 pm. Tim and I were ordered to sit and not move. We sipped wine and watched this unrehearsed production. Alex immediately retrieved the bird and the shears. He cut the breast bone, and he and James took turns trying to level it. Alex finally used all 200 pounds of determination to flatten the turkey. He set it in a dry brine for overnight.

In the morning, Alex cut up all 422 veggies, added the herbs, gizzard and neck and set them to simmer. He and James pirouetted through a combination of sides. The kitchen, rich in aroma, was a chaotic energy: pots bubbling, potato peels flying, vegetables roasting, breadcrumbs waiting to be assembled as stuffing. The stock was done, the burner was needed, and short on counter space, Alex set the hot pot into kitchen sink. On cue, and itching to do something, Tim spotted the pot and before anyone could stop him, he poured soap into the steaming stock. You know that moment when a baby falls and there is no sound before there is a scream? There was no oxygen in the room - right before the wail. The stock was reduced to bubbles.

It's been five years, and if you know boys, well, they haven’t allowed Tim to forget the misstep. (To be fair, if the shoe was on the other foot, he wouldn’t have either.)

Tim and I were recently in Sicily and while there, I signed us up for a cooking class. Though it wasn’t the intimate home setting I’d hoped for, the promise of handmade Sicilian classics like arancini and cannoli made me optimistic.

The instructor was delightful. The room was immaculate with marble countertops set for 16 people. In front of each spot there was a little pile of semolina flour and a beaker of water. She demonstrated making a well in the flour, pouring water into the crater, and mixing it into a mass before kneading it. I was a bit non-plussed by the whole thing, but then I saw the experience through Tim’s eyes. He was fully engrossed and I realized it was a chance for him to experiment without judgment. I never really considered why he was so reticent in the kitchen.

The boys and I were really fortunate to have been brought up in households where we were allowed to “play” with our food. I know my mother wasn’t allowed to. In a family of 10, there were too many mouths to feed, and they literally would have cried over spilled milk. As a result, Mom was nervous in the kitchen. Perhaps Tim too stayed out of the kitchen because he wasn’t encouraged to experiment as a kid—or maybe he didn’t want to risk messing up.

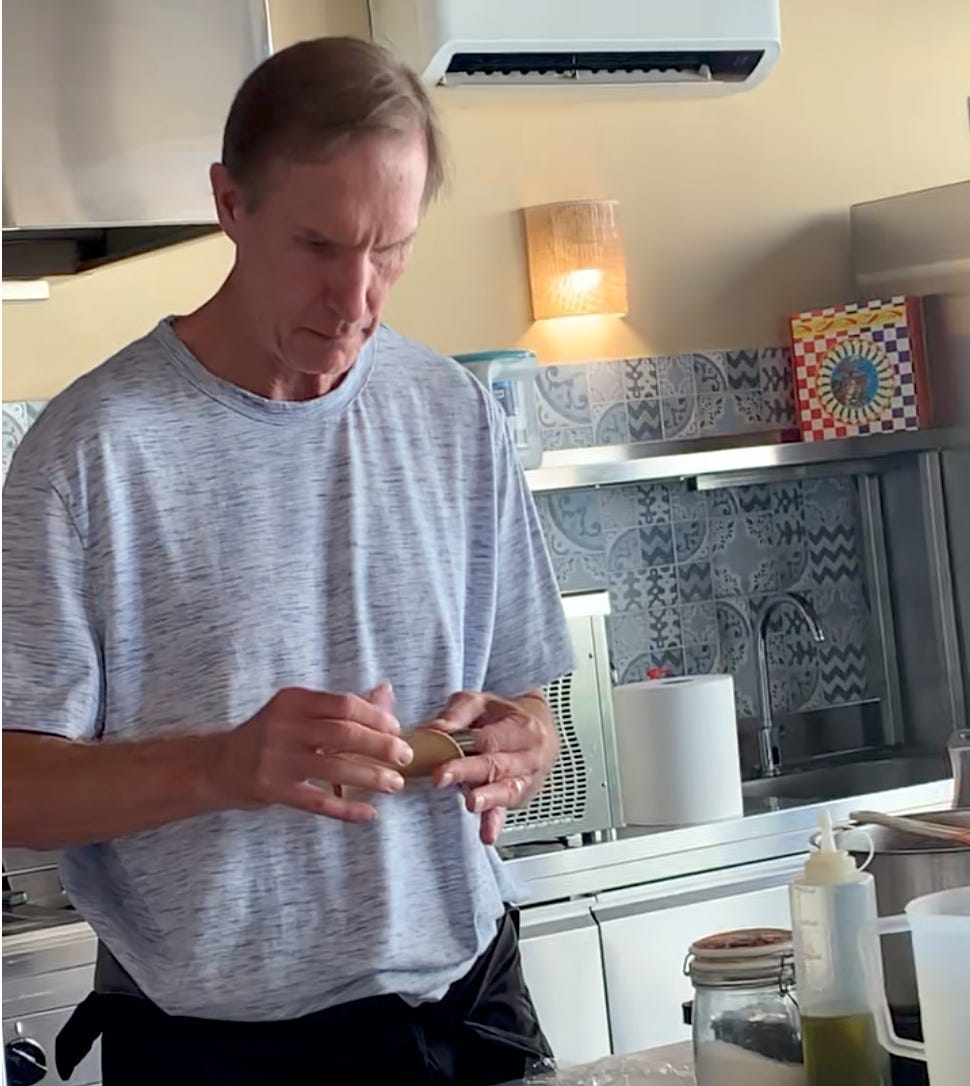

In Sicily, there was no pressure, just a chance to try. Rolling pasta into long strips, shaping penne with skewers—he was laser-focused, like a master craftsman. When it was time to make the arancini. He expertly pressed the rice mixture across one hand, before carefully placing a dollop of meat sauce and cheese in the center, and then enclosing it into a ball.

The last item we made were cannolis. The delicious ricotta filling was pre-mixed. As was the pastry dough – in which I detected a hint of both wine and cinnamon. But she did allow us to use a pasta roller to flatten our dough, cut it, and then shape it onto stainless tubes. The key is to hang the dough from the tube. When you lower the tube into the fryer, the dough quickly expands and it slides cleanly off the tube for filling.

This type of precision is precisely Tim’s jam. Whereas I tend to go too fast, he was methodical in shaping and using a bit of egg wash to seal the joint.

Since we returned, Tim’s comfort in the kitchen is notable. He recently made a cheese and vegetable omelet – and I kept my mouth shut as he prepared it. It inspired me to try something.

Instead of braving the effort for a night out, I set two piles of semolina flour and water on the counter. Tim opened a bottle of Italian wine, and together, side-by-side— deep in the heart of my kitchen triangle—we kneaded dough and made pasta. We even experimented with different shapes.

Standing side by side in the kitchen, his pterodactyl wings safely tucked away, I was struck by how this simple act of making pasta together shows how a relationship can evolve. My kitchen triangle, once a fortress of efficiency and control, now feels more like a space to connect. What once felt like a collision of styles has softened into harmony—not quite a ballet, but certainly a dance we’ve learned to enjoy – even in tight spaces.

What a great pasta adventure and now the two of you are noodling. Loved this essay.

Such a fun story of interacting as a family and in the process, learning more about ourselves and those we love the most. :)