Grounding Lore Into Truthful Narratives

Through the lens of memory, any story can become distorted. How can we ground ourselves—and the stories we tell—into something closer to truth?

As we consume the news, many of us are scratching our heads wondering how facts between two different groups of people can be so skewed. What if the ‘facts’ we inherit—especially in family lore—are less about what happened, and more about how it made someone feel?

A few weeks ago, I wrote an essay where I recount how 20 years ago, in a pique of exhaustion, I fed my two young sons sundaes for dinner. They were not impressed, and after eating their ice cream, asked for dinner. My takeaway from that experience? I was lazy, and filed the memory under something to never do again. So, I was taken aback when my son recently said, “why don’t you write about how Sundays are for Sundaes – and how that led to us making ice cream.”

I’m still stunned.

That essay went further into memories in general. So how can determine if what we think are facts - are actually truths?

It turns out, facts get skewed by how we feel about the fact. In fact, the facts we don’t recall can be telling too. My sister, brother, and I have different, distinct memories of family – that sometimes one of us can’t remember at all. Maybe it’s because for that person there wasn’t any emotional grounding to even register.

Let me give you an example, I’m from Buffalo. When asked if the weather is miserable, I shrug and say, not at all. The temperature doesn’t define the area for me. Summers and falls are gorgeous, winter meant skiing and skating with friends and family. Sure, it snows a lot. But snow plows seem to scoop up the white stuff as it fell. On those rare days when drifts were waist high – it meant no school. Conversely, for people who went to college up there, walking in the elements was pretty trying. They might report the weather is brutal.

“We don’t see things as they are, we see them as we are.”

—Author Anaïs Nin

“It snows in the winter in Buffalo,” generally speaking, is a semantic memory – and “being cold and miserable” is an episodic memory. “Buffalo winters are cold and miserable” is a valid associated fact for some people. The truth lies somewhere in between.

After writing my Sundays Are for Sundaes essay, genealogists reached out to me to ask how the science of memory might apply to family storytelling. What a wonderful observation. Without a doubt, family lore is passed down as “facts” that have been skewed with episodic memories. Stories are a lens on what an individual feels is important. Understanding that gives you an opportunity to look at common assumptions with a fresh lens.

When I was a little girl listening to my great uncles talk about my great-great-grandmother, they referred to her as the Dowager Queen. I got the impression it wasn’t a positive. A dowager is the widow of the king who still thinks she is the Queen Bee. Was she considered a dowager because she was forceful – at a time when women were subservient? Did she have other family that was helping her – or was she on her own?

If you are researching family history, try and ground any assertions – with semantic facts. What was life like in that era? What were some of the challenges they faced? How was their behavior different from others.

Grounding is an interesting word. When referring to electricity, it means safely directing excess energy into say, the dirt, to avoid dangerous jolts or sparks. In storytelling, energy is created when you tell a story; we feed off our audiences. We see what resonates – amplify that – and maybe suppress something else. The “Dowager Queen” probably resonated well with six sons – and six daughters-in-law.

I can imagine it now: the men would laugh and the women would nod about the description of their mother-in-law.

To glean the truth, then, we need to ground “facts” with context, reality, and some sense of self awareness. And grounding the lore with context can create a new narrative. Did great-great-grandmother Rosaria make her own pasta? Did she leave family behind in Sicily? All that little extra give a bit zest to your stories and help ground people in a greater truth.

When I wrote about my great-great-grandmother, I chose a totally different angle. I gave a nod to what my uncles said – but then weighed that against what she accomplished: A woman with six sons -- one of which was born a few months after being widowed, relocates her entire family from Sicily to Buffalo, and then starts up an Italian food store.

I wonder if she had borne daughters if any of them would have allowed that moniker to stick.

I remember another situation, dating back to the 1970s. Two of Mom’s brothers-in-law were very loud. One day I heard them arguing about politics. As a young girl, I thought they hated each other. A couple decades later I mentioned it to my cousins and they laughed and said the two men were the best of friends; when they got together, they loved to drink their beers and debate. A slightly different truth than what I believed.

We like to think that memories are an objective recording. But, like the news, history has a bias.

At a young age, we learn to blur stories into what our audiences wants to hear. It is up to us to look critically at stories or beliefs so as to avoid passing on misinformation or falling for disinformation.

Misinformation happens by accident. Like confusing Leonora Kearney Barry’s mother with her stepmother. Disinformation is more sinister: Disseminators know they are lying – and do so anyway.

In a world where stories swirl faster than we can fact-check, it’s easy to forget that truth isn’t always what’s repeated most loudly—it’s what’s most grounded.

Trust signals provide evidence that the information being given is legitimate. In scientific research, the use of citations is key. This means from a credible journal, from actual people with legitimate titles at real sources. In family history, we are looking at census records (although there might be misspellings) or obituaries.

Absent that, another thing we can do, is look at the lore we inherit. Could there be different points of view – say from a spouse, or a sibling? Would the story hold up if you were able to ask those individuals their thoughts?

Having emotional needs like – wanting your ancestors to be a specific persona, e.g., bad asses, villains, or pious, create fertile environments for misinformation to take root. We can end up projecting what we want with the facts we can find. Like thinking sundaes are for Sundays.

And if we can’t anchor ourselves in truth when it comes to sundaes, how can we do so when the stakes are higher—like history, justice, or identity?

Maybe grounding isn't about nailing every fact, but about anchoring to something real—shared love, values, or memory. Like sundaes over popsicles: one might melt faster, but the other sticks.

Want more on Memories?

I am so very pleased to announce that

asked me to dig deeper into unearthing truths about family lore. She reached out to me after reading my Sundaes Are for Sundays and invited me to do a Live with her. I am so excited and absolutely honored to be presenting to the many historians and genealogists who follow ProjectKin!The two of us will be dishing about memories - faulty and otherwise, and how we might ground them in truths.

You can join us on

July 27th for a Live Preview with

and me.

and then on

July 29th: The Scoop on Memories with Diane Burley

Bring your questions, happy to give actionable advice so you can create absolutely delicious narratives – that don’t have any of the calories of a sundae. Register at the links above.

So happy you are here reading these essays.

I have a favor to ask, please hit the heart button below - or leave a comment.

That’s how others find my work. Thank you!

What I am Reading

Absolutely enjoying the wry wit of George Eliot in Middlemarch as she narrates life in early 19th century England. The status of women, expectations of men, mores and hypocrisy of the time are all on display.

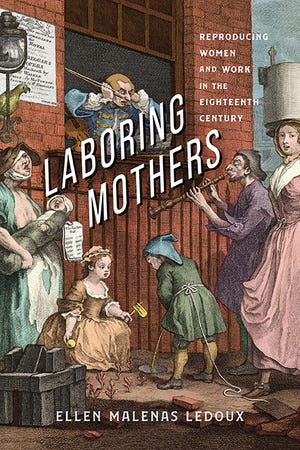

I’m going to stick with the time period with my next selection of reading: Laboring Mothers, by Ellen Malenas Ledoux.

Hi 👋 Diane,

My mother's cousin wrote a book. In it, he described each of his aunts and uncles. He wrote that his aunt, mom’s mother, woke up out of a coma to correct somebody’s grammar.

I asked my mom about it, and she said that her mother didn’t wake up out of a coma. She was just coming out of anesthesia after surgery.

I guess people were standing around her in the hospital saying, “Look at her just lay there.” They kept on talking about her “laying” there. She woke up and said,”The correct word is lie.“

But what is true is that my grandma was very good at grammar. So that if his version gets passed down the generations, the general notion will be that she was very good at grammar. That isn’t the same as emotion, but it is a trait.

I really appreciate the way you cleverly illustrate the difference between semantic and episodic memory and between misinformation and disinformation. I got a chance to listen to some of the conversation with Barbara at ProjectKin, but only this morning got a chance to read this in full.