The Immigrant Who Did Something

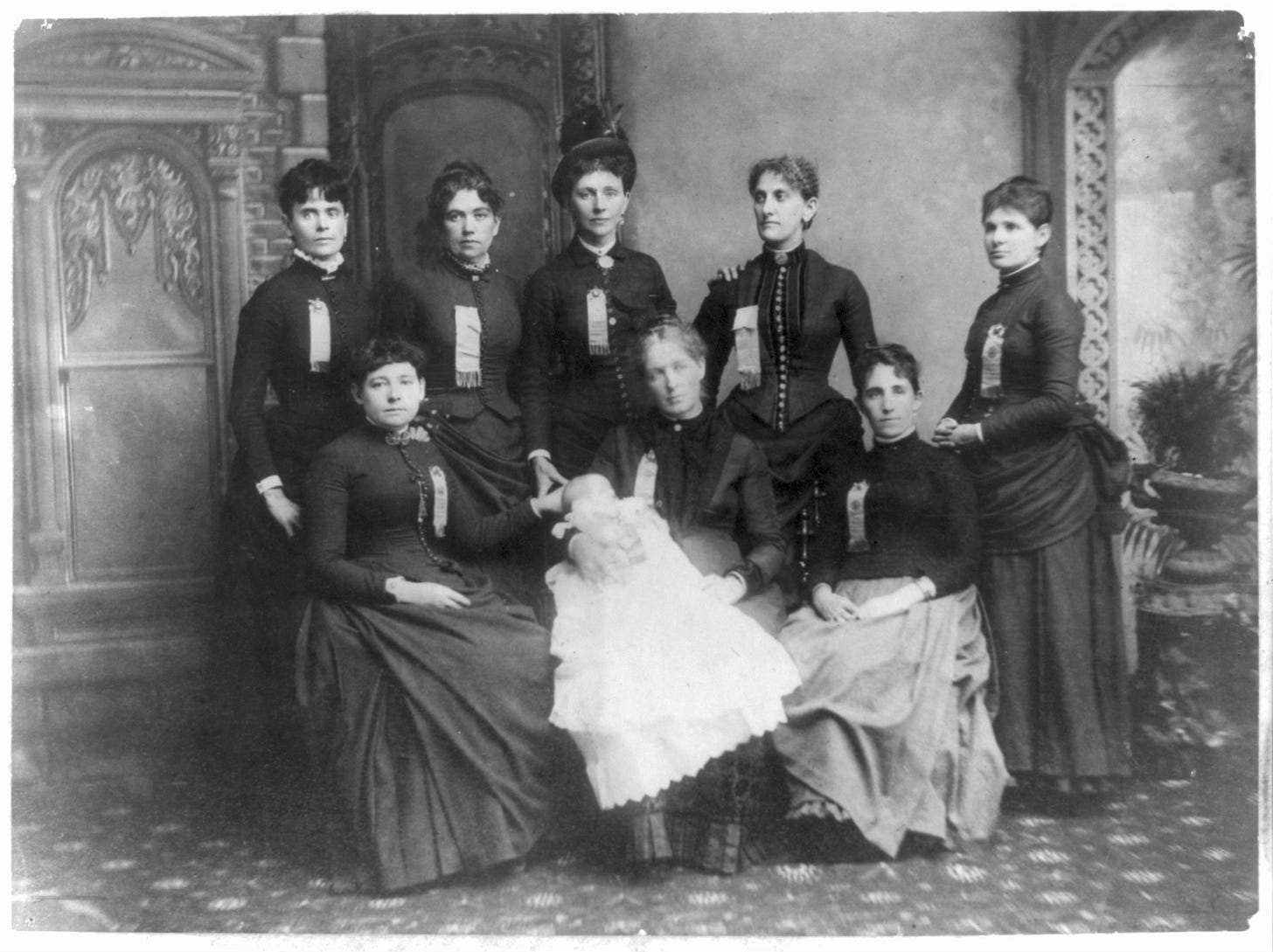

Widowed with small children, Irish-born Leonora Kearney Barry, was a leading voice and advocate for workplace reforms for women and children.

“Why doesn’t someone do something?”

It’s a chorus we sing whenever life gets grim. And lately, there’s … a lot. Citizens dragged off the streets. Prices through the roof. Supreme Court run amok. Uncertainty about everything. It’s human nature to want someone, anyone, to step in and say,“I got this.”

Let me tell you a story — a true one — about a woman who did step in.

She traveled thousands of miles, gave hundreds of speeches, put up with fetid conditions —confined by nothing but her corset.

To do something.

By herself.

More than 135 years ago.

Oh, and she did this as a single mom – and as an immigrant without formal education.

Back when Irish Catholics were particularly despised, Leonora Kearney’s family emigrated to the United States to settle in the North Country of New York when she was 3. Honora Browne Kearney, enjoyed the vestiges of noble lineage (even if it was no longer recognized) by being highly educated and fluent in seven languages.1 John was a farmer from the Cork area, and after the potato famine, settled among brothers and cousins on Irish Settlement Road in Pierrepont, NY. My great-great-grandfather Daniel was one of those relatives.

Despite his wife’s education (or maybe because of it) John didn’t see the value of sending a girl to school. Begging to learn, Leonora studied math, the classics, poetry, and languages “at the knee of her mother.” Sadly, her mother died when she was 15. A year later, her father remarried, and Leonora studied to become certified as an elementary school teacher. Meager wages forced female teachers to board with families. After a few years, Leonora left teaching to learn dress making. She met William Barry and they were married in fall of 1871.

The couple left the North Country to the fairly bustling city of Amsterdam, located on the Erie Canal, which ran alongside the Mohawk River. For a decade, life was pretty good. William was a house painter during the week and a band leader on weekends and holidays, giving the Barry family a bit of gravitas. Leonora took in sewing for “pin-money,” no doubt to splurge on her children.

But as was common at the time, William died of tuberculous (TB), and their eldest, a daughter, passed away a few months later.

Leonora later described the terror she felt after her husband died.

“I was left, without knowledge of business, without knowledge of work, without knowledge of what the world was, with three fatherless children looking to me for bread.”

Ah, that social construct. Once a woman married, she was banned from teaching. Looked down upon for earning. When death upsets the norm, there is no quaint solution. Mending might be pin money but not enough to sustain life. Some widows took in borders, but when William became sick, the Barry’s downsized. When he died, they moved into even smaller accommodations. Desperate to earn a living, Leonora was forced into working for a nearby hosiery mill. A very unladylike task.

Work in textile factories in the late 1800s was grueling: Massive machines left little room for humans, creating unsafe conditions for anyone with scarves, long hair, or long dresses. Steam-powered spinning and weaving devices created chokingly hot working conditions. Working in dimly-lit rooms with lint-filled air amid the deafening roar of looms created high risks of blindness, mouth and lung cancers, and hearing loss. Oh, and men were lecherous.

Pay was often piece rate – based on the output. Leonora made 11 cents her first day, and 65 cents for the whole week - despite working nearly 70 hours. I wondered who took care of her children and found an article that said she relied on neighbors. Isn’t that what we do? When life is tough, we rely on our community to help us out. I’m certain that in exchange, she watched their children, taught them lessons, or perhaps mended clothes.

As a mother, former school teacher, and channeling her own disappointment of not going to school, Leonora was outraged when she saw tiny children conscripted to spend their days squeezing into tight areas to change bobbins on machines that regularly snatched slow-moving fingers.

Leonora joined the Knights of Labor (KoL) a federation for skilled and unskilled workers that emerged in the mid-19th century. Unlike typical unions that were reserved for white (usually Protestant) men and focused on a single trade, the KoL included women, all races, and ethnicities.

A rousing orator, Leonora rose quickly in the ranks becoming president of her local chapter of 1,500 female knitwear workers; then president of District Assembly 65, which represented 52 locals and a total membership of over 9,000. And finally, National Inspector. At the national conference in the fall of 1887,2 her impassioned recounting of abuses including excessive fines, low wages, and demands by men on young women, impressed them to create a role for her to investigate factory conditions and pay for women and children on a national scope.

Her salary more than quadrupled, but it required her to travel across the country and into Canada. She sent her youngest to live with in-laws in the North Country and sent her older son to a convent boarding school. Over the next 12 months she traveled thousands of miles – by rail, steamship, stage coach.

She showed up: in Troy, in Toronto, in Toledo, maybe even in tears -- but she showed up. Carrying a carpet bag – without rollers. Navigating cobble stones and dirt paths, in boots and a corset – but always with her signature hat.

And she brought the receipts: In Cincinnati, workers netted 25 cents a dozen for undergarments trimmed with ruffles or lace; in Cohoes, NY, waitresses earned $2.50 a week - but a chipped dish cost them 25 cents; in Philadelphia, woolen mills employed children as young as 12, and fines for being even 5 minutes late were excessively large.

She noted that mills that had organized were offering fair wages and better lighting. Of course, like today, some owners were hellbent to punish organizers – some offering bounties of $25 to snitch. As word spread that Leonora was investigating factory conditions, foremen began punishing those who spoke with her. When she couldn’t get into a location – she spoke to crowds in churches and public spaces (though, never pubs). She spoke about the KoL, about the importance of child education, about poverty, about disease. If she had an audience and a topic, she prepared a speech. In all, there were 537 requests for her to come speak – of which she filled 213.

In a year.

To say she was tireless is an understatement. I traveled a couple days each week for work. With luggage on wheels, modern trains, flights, and FaceTime with the kids—I was exhausted. She had none of those things.

On top of that, she was a one-woman marketing department lauding the benefits of organizing, increasing numbers in some cities, gathering research, and analyzing data. One woman.

And her efforts paid off. With her son in Philadelphia, she spent much of her free time there, so it was probably not by accident that her focus was on the city and state. She prepared a bill for the state legislature to establish a factory inspector to root out child labor. It would eventually pass virtually verbatim.

She presented her reasoning at the 1888 KoL conference, Leonora’s fury was palpable.

Her motivation was “on behalf of the little ones of this rich and thriving state, 200,000 of whom are deprived of the privilege of common school education, and 125,000 of whom are employed in its workshops, factories, mines and Mercantile industries. There are many evils, attended upon the employment of children, particularly girls, which leads to misery, ignorance, and despair. Accustom is rapidly increasing in this country, which means shame, dishonor, and humiliation to womanhood.”

As was common at the time to maintain propriety, Leonora’s language around sexual assault and sexual coercion, is delicate and thus vague. When asked why women don’t come forward, she wrote:

First, because those who resent such pernicious approaches shrink from giving publicity to their humiliation, and those who do submit will not make their misfortunes public, until perhaps, they can no longer hide their shame.

But because it is so delicate, let me paraphrase Leonora’s 1888 language in 2025 parlance:

I found that in most cases when a woman is sexually abused, especially a young woman, making it public only adds humiliation – and no doubt, doubts about her word. Instead, she remains silent – unless the “effects” of the abuse, her pregnancy, can no longer be hidden.

And we wonder why women don’t speak up.

As a means of educating the public she pushed too, for goods to have a label – KoL or otherwise, indicating the goods were made by a fair-minded employer.

In her mind, it was more than just wages. In her analysis she equated the long hours, physical demands, unsanitary conditions, and lack of proper nourishment (from low wages) with being severely injurious to women – and the foundation of our country. The germs a woman picked up would be passed to the family – the men and women of the future.

And that was the crux of it. Leonora saw fairness – as patriotic to the needs and future of the country. At a macro level, what this native from Cork, Ireland, did is nothing but astounding. Under a microscope, with nothing more than her own convictions - and the need to feed her hungry children, is other worldly.

In looking for someone else to save us we forget about our own power. It only takes one person with conviction to revolutionize change.

I so glad you are enjoying this piece, and will continue to keep write without a paywall. May I ask a favor? Could you click the heart below, leave a comment, or share with a friend? This is how others will learn of my work. Thank you!

What I Am Reading

Enjoyed learning more about the many outstanding women from my hometown in The Spirit of Buffalo Women, by Rick Falkowski. I am sticking with the 19th century with George Eliot’s Middlemarch. Eliot wryness toward conventions is apparent from the first chapter. No wonder it ruffled a zillion feathers when it was written.

An 1890 article in Locomotive Fireman’s Magazine reported that Leonora’s mother came from “English ancestry and noble lineage … though suffered impoverishment through the fickleness of fortune.”

All statistics are taken from the Report of the General Investigator of Women’s Work and Wages, at the General Assembly of the Knights of Labor of America, Twelfth Regular Session held at Philadelphia, PA Oct 15, 1888.

Thanks for showing us again that amazing things can happen when one person chooses to act.

Fascinating profile of Leonora. Your voice -- strong and clear -- pulled me right in to her story.