The Human Cost of Tariffs: Lessons From Labor in the Gilded Age

Tariffs are a tool to protect domestic industries - ostensibly to benefit American workers. History shows us though, that when wrongfully enacted, tariffs can hurt the very people we want to help.

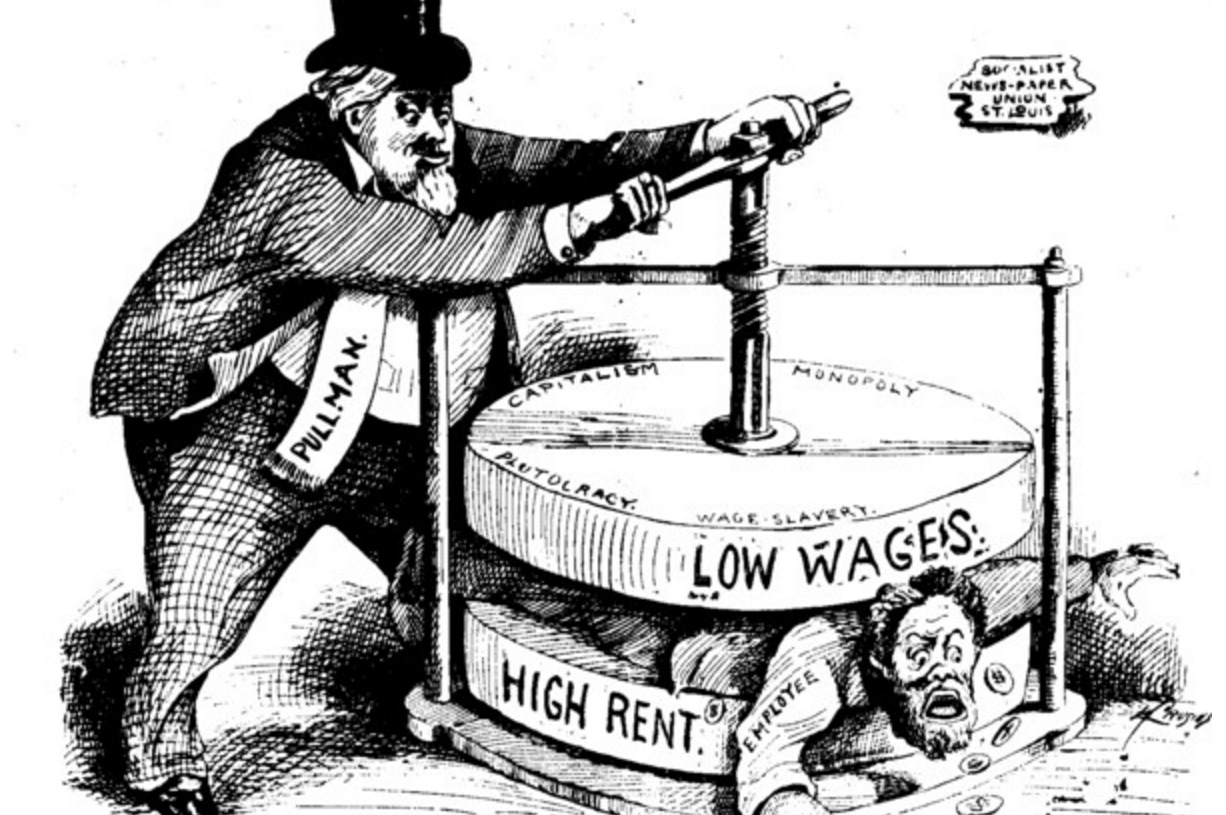

Tariffs, long promoted as tools to protect domestic industries, often end up enriching a small elite while harming the working class. History shows us that such economic policies, can create conditions of exploitation and dehumanization that reverberate across generations.

On Oct. 5,

did a splendid job talking about the impact of the McKinley tariffs of the 1890s. That time period is often referred to as the Gilded Age. Industrialists like the Vanderbilts, Astors, Carnegies, and Rockefellers amassed huge fortunes and feathered their nests with ostentatious ornaments and came to define the “Haves.”As Richardson aptly pointed out, initially, tariffs helped create a booming post-Civil War economy by protecting burgeoning American industries. However, as time passed, the same tariffs served big business by shielding it from competition and allowing manufacturers to collude and keep prices high.

This protectionism benefited factory owners, but for the working class—new immigrants and recently freed slaves—it meant fighting for economic survival. By the 1890s, the wealthiest 1 percent of American families owned 51 percent of the country’s real and personal property. Not surprisingly, as the economic fortunes tipped the scales in favor of these social elite, the preponderance of the working class – faced a bleak existence.

As there is chatter once again of revisiting similar economic strategies, it’s critical to understand the human cost of blanket tariffs. Just like in the 1890s, policies aimed at protecting industries often funnel wealth to a small elite while pushing the majority to the brink of poverty.

In June 1889, Andrew Carnegie penned The Gospel of Wealth, an article that could be used today as a backgrounder for Sunday morning television in defense of unfettered capitalism.

While he argued that wealth should be used for the good of society, he shrugged off the possibility of achieving true social equity, stating:

it is not practicable in our day or in our age. Even if desirable theoretically, it belongs to another and long-succeeding sociological stratum.

Carnegie’s dismissal of social responsibility in 1889, is eerily similar to today’s economic discussions, where calls for increased worker protections are often framed as threats to “business efficiency” and “market competitiveness.” The rhetoric may have evolved, but the underlying argument remains: profit margins matter more than people.

And as Carnegie justified the existing inequalities with intellectual arguments, tariffs created a tax on purchases of almost 50%. Workers like Leonora Kearney Barry faced the brutal realities of industrial exploitation; wages were stagnant and far below what it took to survive.

Leonora was a young widow who was forced into factory life to feed her children. Disgusted with unsafe and unsanitary conditions, in 1897 she became a labor activist for the Knights of Labor (KoL) - a predecessor to modern unions. As General Investigator for the Department of Women’s Work for the KoL, Leonora’s role was to interview and document conditions in factories and mines across the country.

Her notes were painstaking with details1:

The abuse, injustice and suffering which the women of this industry endure from the tyranny, cruelty and slave-driving propensities of the employers is something terrible to be allowed existence in free America.

Women are compelled to stand on a stone floor in water the year round, most of the time barefoot, with a spray of water from a revolving cylinder flying constantly against the breast; and the coldest night in winter as well as the warmest in summer those poor creatures must go to their homes with water dripping from their under- clothing along their path, because there could not be space or a few moments allowed them wherein to change their clothing.

May 12, returned to complete the work mapped out for me in D. A. 99. Summing the State of Rhode Island up, on the whole, the condition of its wage-workers is truly a pitiful one its industries being for the most part in the control of soulless corporations, who know not what humanity means-poor pay, long hours, yearly increase of labor on the individual, and usually a decrease of their wages, the employment of children, in some cases, who are mere infants.

She was blunt with her criticisms:

The price paid for all kinds of women's and children's wear, also that of men and boys, manufactured on the slop-shop system, is simply a means of slow starvation, being insufficient to procure the amount of food necessary to appease the pangs of hunger, much less pay the exorbitant rent for their miserable tenement to the pitiless landlord, or cover the wasted form with comfortable clothing.

Policies that focus solely on profits lead to the exploitation and dehumanization of workers. When people are so poor and dependent on a paycheck, they can’t push back against dangerous working conditions.

Just as workers in the 19th century were forced to choose between their safety and keeping their jobs, today’s immigrants face similar pressures.

During Hurricane Helene, immigrants at a Tennessee plastics plant were told they could not leave despite a hurricane barreling down on them. With the parking lot flooded and water seeping into the building, the owner finally gave permission to leave. Tragically, it was too late. At least five perished and one person is still missing.2

The disregard for worker safety during Hurricane Helene echoes the infamous Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire of 1911. In that incident, 146 workers—mostly young immigrant women—died after being trapped in a burning factory because the doors were locked to prevent theft and unauthorized breaks. The tragedy catalyzed reforms and increased workplace safety regulations, but it took an unimaginable loss of life to spur change.

Over a century later, as Hurricane Milton bears down on a decimated area, similar dynamics are at play. Workers are being asked to prioritize their jobs over their safety. A relative of mine, in the path of the storm, was told to come into work for a few hours before evacuating.

Economic growth should not be measured only in profits, but in how well it upholds the dignity of every person who contributes to it. As history has shown, the cost of prioritizing profits over people is often too great for society to bear.

Knights of Labor. General Assembly. Proceedings of the General Assembly of the Knights of Labor of America. Minneapolis, Minn.: General Assembly

Our North American obsession with "The Economy" at the expense of all else is something that is so distasteful about our current version of capitalism (among other things). Measuring and focusing on profits and GDP as the standard of wealth and success leaves such a huge gap in our human potential.

I see it on a personal level as well as national, people who consider themselves unsuccessful because they don't have the status quo financially, meanwhile they have an amazing marriage and family relationships, health, and a meaningful life.

I wish some other form of measuring success besides finances would really take off in our culture. Nationally there are even other proposed options to the GDP:

https://www.stlouisfed.org/open-vault/2023/apr/three-other-ways-to-measure-economic-health-beyond-gdp

Great article! I've been thinking about Trump's reference to McKinley and proposed tarriffs all week. Leonora's observations of working conditions then continue to make the case for protection of workers, not for the protection of profits.