Sicilian Caper

Forty years ago, I traveled to Sicily to trace my ancestors' heritage. This time when I went, I uncovered how it shaped who I’ve become.

It’s impossible to believe it’s been more than 40 years since I was last in Palermo. At the time I was a poor exchange student who had been living in London. Finished with classes, my roommate Debbie and I donned backpacks and grabbed Eurail Passes. The passes gave us the flexibility to jump on and off trains as we wanted. We saved on lodging by hopping on a train at night and picking a location far enough away so we could sleep until morning. We didn’t travel through Europe; we criss-crossed it.

After a month, Deb and I decided to split up. She headed to Israel and I trekked to Sicily. Spurred by lore spun by my great uncles, I headed to see my great grandfather’s hometown of Termini Imerese, located near Palermo on the north coast. Per usual, I fell asleep on the train, only to be urgently awoken by someone in authority. He was yelling and motioning me to get off the train. People pushed and shoved. Rattled and groggy, I grabbed my backpack.

Stepping off the train, the platform signs said Messina — the toe of the Italian boot. I disembarked into surreal chaos. People with cardboard suitcases tied up with twine were pushing and shoving. Chickens scurried around my feet. There were a few cows and a donkey. Barnyard smells were overwhelming. I’m only 5’2” but I recall towering over all this confusion. The train needed to be loaded onto a ferry, and so the cars were detached and loaded in groups. Some of the original cars didn’t make the cut. When the cars were situated we had to once again find seats. Exhausted, I fell back to sleep.

When the train reached Termini Imerese, a vendor was selling thimble-sized paper cups of coffee that was as thick as syrup - and deliciously sweet. Cafe was one of the few words I knew. My college-level French had been sufficient for most of my travels, but in Sicily it was useless. My Dad’s mom, Nana, had warned me that the Sicilian dialect was very different from Italian. I panicked a bit wondering how I’d get around.

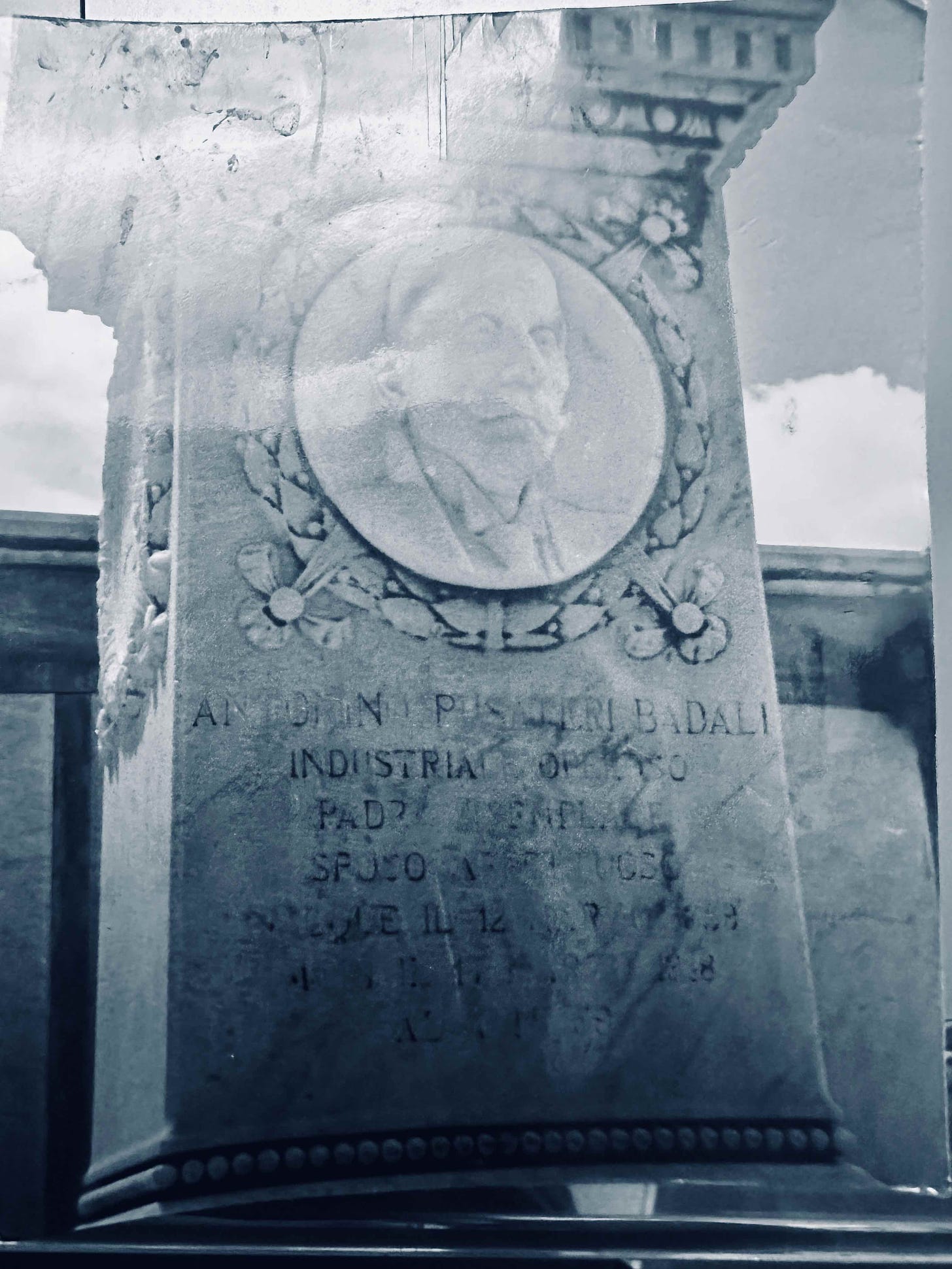

The trend at the time was to sew patches onto your backpack to indicate where you were from - and where you had been. It was a great way to meet people. I was eating a gelato and a creepy man in a white suit and white fedora was hovering. Three people my age - one of whom spoke English - came to my rescue, and the creepy man disappeared. I shared my mission: to find out more about my grandfather’s ancestors. My new friends drove me to the Cimitero Comunale Di Termini Imerese, where I found the gravestones of my great-grandfather’s father – and his father. I still have the grainy photo.

We didn’t stay long as my tour guides were restless. We went into town, and stopped at what literally was a hole in a stone wall, and a man appeared with drinks and a variety of potato and cheese croquettes and arancini - deep fried rice balls filled with meat, cheese and peas. Wandering again, I saw older women clad in black (a sign of widowhood) dodge us to disappear behind thick wooden doors. Younger women, not more than girls, wore bright crop tops and cut off shorts and sat on the back of mopeds. When salt meets fresh water we call it brackish, do we have a word for when the ancient fuses with modern?

Transported through history, I fell in love and promised myself I would get back to explore some more.

Fast forward a lifetime, and my husband and I flew into Palermo. With databases at my fingertips, there wasn’t a need for a second visit to the graveyard. The old women in black - and the Sicilian language itself were all missing - as only Italian is taught now in school. Moving around the streets of Palermo, I wondered if my memories were faulty. We didn’t have iPhones to memorialize every step. And my instamatic, groundbreaking in its time, didn’t do justice to the subjects.

But the markets were still lively - and the people still short! People pushed and shoved to get closer to the fruit, cheese, and fishmongers. A stall showcased sardines, swordfish, tuna, octopus, and grouper resting on beds of ice - with their mouths agape and their eyes staring. That contrasted with tables filled with packaged food products; seemingly endless varieties of jarred spreads: pistacchiosa, mandorla (almond), nocciola (hazelnut), and lemon creme. In fact, while the prickly pear is the national fruit, the mighty lemon was everywhere - limoncello, candies, candles, soaps - and on aprons, potholders, bath towels.

The modern had evolved. Of course, the ancient was still there.

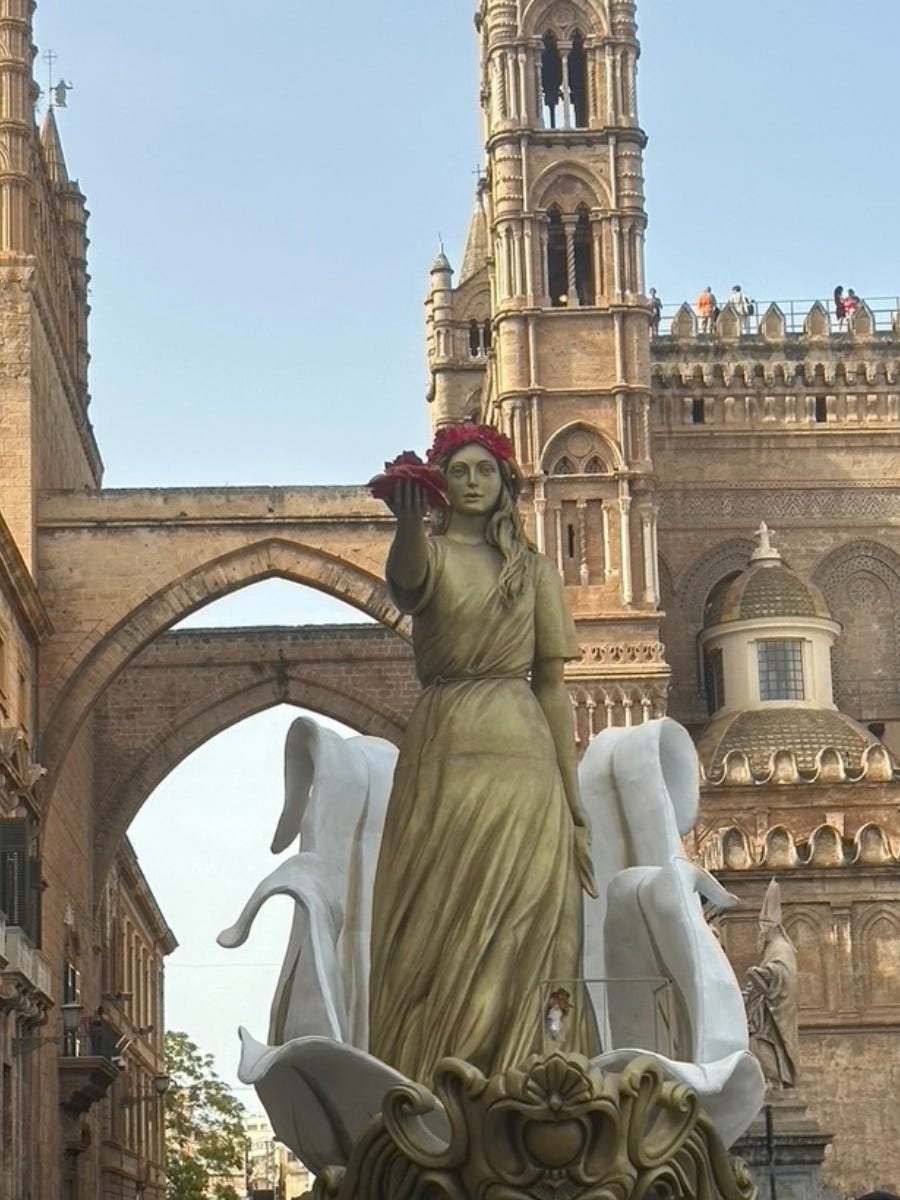

Unlike in my impoverished youth, this time I visited a multitude of historic sites. We wandered the cobblestone lanes made of marble (how did they cut them so uniform - and who designed the intricate patterns?). More than once I felt Tim and I were on a film set with a variety of ocher-colored concrete houses, wooden doors and shutters, and elaborate metal balconies. The cathedrals were simply amazing and rich with details.

Sicily was once a trade hub for food products and textiles between North Africa, Egypt, and eventually Europe. This attracted money - and conquerors. The Greeks were pretty good inhabitants - adding classic Greek temples and monuments. The Romans, on the other hand, pretty much ransacked the area. After Rome fell, its successor, the Byzantines (Eastern Europe) came. Greek culture - language and art - again dominated the area. Temples became basilicas featuring ornate mosaics with gilded adornments (tesserai).

Next came the Arabs of North Africa. They left the underlying structures, converting them to mosques, added domes, African artwork, courtyards and parks. Finally, the Normans came - the French. They converted the temple-basilica-mosques into Roman Catholic churches and added enormous towers to the religious structures. Each successive invader built upon the cultural contributions of the predecessors. The resulting new architectural style of Arab-Norman, presents layers of intricacies that make replicating it (or describing it!!) near impossible.

UNESCO designates historic palaces, churches, and monuments as World Heritage Sites for its fusion of empires - Norman, Arab, and Byzantine. There are several of these sites in the Palermo-area alone.

Our bed and breakfast was nestled between two such structures - Norman Palace and The Cathedral of Palermo. The spacious grounds were covered with palm trees, and the cathedral’s lit tower guided us home every night.

And just outside of Palermo, a short bus ride away, is the Duomo in Monreale. It wasn’t yet open, so as we walked the cobblestone streets we saw a bistro that was situated in an ancient wall. Wooden barrels flanked the doorway. We pulled stools around one. I ordered an antipasto that featured three spreads: olive tapenade, whipped ricotta, and a caponata. I broke a chunk off a loaf of bread and lathered it with the tomatoey caponata.

If you have never had it, think of caponata as a cross between a salsa and a relish in consistency. It’s a melange of fried or roasted chunks of eggplant, celery, onions, tomatoes and peppers heated together. Some recipes add in a bit of sugar or honey to provide that syrupy texture. But what makes it stand out are the olives and capers.

A caper is about the size of a pea and is the unripened bud of the caper bush, a perennial that grows in the mediterranean. Apparently, if you pick them right off the bush they are bitter. But if you dry them in the sun - and pack them in a brine, they are deliciously salty. I just open a jar.

I bit into a briny caper — felt a wave of melancholy. It was 30 years prior and I am in Nana’s kitchen. She was frail but determined to put out a spread for Tim and I. She hauls out a lasagna that I thought might topple her over, and a container of her caponatina. (I think she called it capona-tina - because she cut her vegetables into finer pieces – like a relish.)

While her own parents had emigrated from Naples, much of Nana’s cooking reflected more of the culinary style of her Sicilian husband, my Poppa. She scoffed when eggplant and olive oil made its debut on American menus in the early 1980s. “Average people have been eating this for centuries,” she sniffed, “and now it’s gourmet.”

Over the years, I’ve sampled numerous versions of caponata, but I have found it either too bitter or too sour. But this one was just like Nana’s. Was there a hint of her Neapolitan heritage in her version?

“I don’t have a recipe,” she told me more than once. She handed me an index card, “Here are the ingredients. I put in a handful of this, and a handful of that.”

I need to find that index card, I thought. I took another bite to savor the connection to my family.

After lunch, we headed to the Duomo. It was so much more ornate than the one by our B&B. Historians say that almost 5000 pounds of pure gold were used throughout the structure.1 I squelched uncomfortable thoughts of the expense – and how that money might have been used to help people – and instead appreciated the blending of the cultures.

Over the next week we saw more examples of a veritable caponata of cultures - and Sicily’s appreciation for multiculturalism.

This blend of cultures and history mirrors my own heritage — a fusion of the old and new, the familiar and foreign, and different nationalities. As I walked those ancient streets and enjoyed that familiar caponata, I realized I wasn’t just revisiting a place. I was reconnecting with the past, feeling the weight of generations, and the countless layers of history that shape who I am today.

Just as Sicily interlaces the legacies of those who came before, I too am a braid of my ancestors—the flavors, the stories, and the spirit that have been passed down. Forty years ago, I fell in love with Sicily. This time, I found a deeper love for the connection it offers to the parts of myself that I hadn’t fully appreciated before.

Esplora Travel. Monreale Cathedral.

What an exquisite black and white photo of the Duomo! Siciily 40 years later, you could really appreciate it in a new way. And I got hungry reading about the delicious food.