My Emotional and Familial Connection to Labor Day

Through my great, great grandmother's cousin, I have a renewed understanding of where we have come as a society when it comes to honoring workers on Labor Day – and where we still need to go.

It’s Labor Day, and research I have been doing on my great grandmother’s cousin has me thinking about the progress we have made – and the work we still need to do.

Widowed at 30 and after only 10 years of marriage, and with three little children, Leonora Kearney Barry didn’t know how she would make a living. That was never supposed to be her problem. Husbands were supposed to provide. In fact, she was forced to resign her post as an elementary school teacher as soon as she married.

Worse, shortly after her husband died, her 8-year old daughter passed. Her two surviving sons were only four-years old and six months, and the baby was sickly. Thrust into this grave new world, she did what many widows did at that time – took in sewing and borders. But it wasn’t enough to get by.

It was 1881, and Leonora was living in Amsterdam, NY, a benefactor of the Industrial Revolution. The town was crowded with mills that sat along the Hudson River and near rail yards for easy shipment of goods. Factory owners were hungry for cheap labor. Leonora took a job with a hosiery mill, working six, 12-hour days. They paid her by the finished piece. Not knowing how to work the machinery she took home 11 cents her first week. As she became proficient with the machinery, her weekly wages rose to 65 cents. A wage barely above starvation.

As a working mom whose husband often traveled, my first thought was, who took care of her boys? It wasn’t well documented, but I did learn that her husband’s family in Potsdam, NY, took the baby, while the older boy was sent to a convent school in Philadelphia. By car, it would take hours to get from one city to the other. With trains, steamers, and stage coaches, how often could this former stay-at-home mother see her children?

Working in a factory horrified her. It was unsanitary and crude. Men were vile around the young female workers. It was also unsafe. She had to hold her long skirt around her to keep from being sucked into the machinery. Bits of thread and fabric lint filled the air causing lung ailments. Children as young as her son changed bobbins and swept floors. Leonora described the rules for workers, and fines if they weren’t followed.

[In the] corset factory … a fine is imposed for eating, laughing, singing or talking of 10 cents each. If not inside the gate in the morning when the whistle stops blowing, an employee is locked out until half-past seven; then she can go to work, but is docked two hours for waste power; and many other rules, equally slavish and unjust. Other industries closely follow these rules, while the sewing-women receive wages which are only one remove from actual starvation.

Leonora’s parents, like my great grandmother’s, were natives of Cork, Ireland. They all relocated along the lush St. Lawrence River, in Northern New York. At the time of her husband’s death, labor reform had been going on in Ireland for almost 50 years. The United States was way behind.

After two years of factory work, Leonora learned of the Knights of Labor (KoL) and its slogan “Equal Pay for Equal Work.” Its slogan wasn’t the only allure. While its members were mainly men, unlike unions, the Knights were the first national labor organization to bring together different trades and to admit women and men – of all races – as equals.

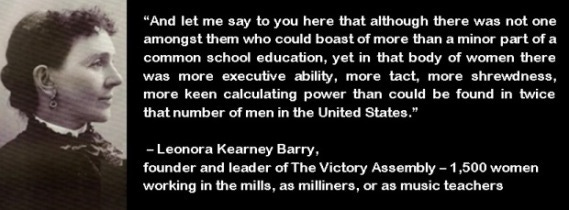

Leonora joined her local, the victory assembly, which included many of the female employees in carpet and hosiery operatives, dress makers, milliners, and music teachers in Amsterdam. She attended meetings, listened, and took extensive notes. But her life changed after she attended the KoL convention in Richmond.

With my observations, and knowledge gained here of the conditions under which women were working, I went before a convention of the KoL in Richmond in 1886. Not only did I get a hearing, but an office was created for me in which I was to investigate conditions of women’s labor throughout the United States.

Change is near impossible without data. In modern day management, the mantra is, if you can’t measure it, you can’t manage it.

For the next three and a half years Leonora gathered data on the prevailing hourly and weekly wages, average and range of hours worked per day, by both men and women, segmented by type of work, as well as the retail price of the finished product. She knew the laws, she learned of the abuses, and wrote lengthy reports.

By the end of that decade, Leonora would be the U.S.’ leading voice for women and children.

As the General Investigator for the Department of Women’s Work for the KoL, and with her intimate knowledge of employees, Leonora documented the appalling conditions within factories.

The abuse, injustice and suffering which the women of this industry endure from the tyranny, cruelty and slave-driving propensities of the employers is something terrible to be allowed existence in free America.

Women are compelled to stand on a stone floor in water the year round, most of the time barefoot, with a spray of water from a revolving cylinder flying constantly against the breast; and the coldest night in winter as well as the warmest in summer those poor creatures must go to their homes with water dripping from their under- clothing along their path, because there could not be space or a few moments allowed them wherein to change their clothing.

Her reports rankled factory owners who banned her from their premises. Anyone who helped her gain access to a factory floor was fired.

While she fought for women’s wages and better labor conditions for all, she lobbied harder for the rights of children, who earned a fraction of adults. Its possible she saw in the toiling youngsters her own children. Or perhaps, as a former teacher, she knew these children were being robbed of the chance of a better life by not attending school.

More than a million children worked 10-11 hour days. Her recommendations to the general assembly included urgent appeals for child labor laws, state factory inspections, and abolition of sweatshops.

She traversed the country: Colorado, New Jersey, Missouri, Ohio, New York, Massachusetts, Connecticut – and gave hundreds of presentations to make people aware of poor working conditions. She was blunt with her criticisms.

Summing the State of Rhode Island up, on the whole, the condition of its wage-workers is truly a pitiful one its industries being for the most part in the control of soulless corporations, who know not what humanity means – poor pay, long hours, yearly increase of labor on the individual, and usually a decrease of their wages, the employment of children, in some cases, who are mere infants.

Her audiences included the aristocrats of society, the International Council of Women, elected officials, and union leaders. In January 1889, she spoke to the Pennsylvania legislators at Harrisburg urging them to vote for her factory inspection and child labor bill. A bill reining in child labor in Pennsylvania, the first of its kind in the nation, became a law May 20,1889.

The Women’s Department of the Knights of Labor was defunded that year and Leonora left the organization. Remarried and reunited with her children, she relocated to Missouri – yet continued traveling the country speaking on labor reform and temperance. She spoke in front of packed crowds.

People who knew her described her as a tall, witty, and gifted orator. She attributes her talent to her mother.

My education was gained not at the knee of my mother … but through contact with her superior gifts and attainments. My mother was a highly educated woman - mistress of seven languages and rarely-gifted in the quality of motherliness.

It would be another 40 years before the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 (FLSA) was passed - a law that restricts the employment and abuse of child workers. In 1940, the 40-hour work week became law. It was 1964 before a law was passed that allowed married women to keep their jobs.

I was one of the lucky mothers who had six weeks paid maternity leave when my first son was born. And four weeks after my second son was born, my employer terminated my position while I was on family leave. That violation allowed me to collect six-months severance.

For all of our progresses, over the past couple years, there has been an organized movement to undo the regulations that my first cousin four times removed fought for.

Since 2021, more than 60 bills in 30 states have been introduced to lower minimum age requirements, remove mandates for minimum wage, allow children to work in hazardous conditions, and extend work hours. Seventeen of these bills have passed in 13 states. Project 2025 proposes the elimination of federal protections for workers.1 The states that have rescinded laws have already seen child fatalities:

16-year-old pulled into a machine at a poultry plant in Hattiesburg, Mississippi — the second fatality at the facility in just over two years

16-year old in Wisconsin died after being entangled with a machine

Teenage boy in Pennsylvania died after being pulled into a woodchipper.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, 57 children under the age of 16 and 68 teens between the ages of 16-17 died on the job between 2018 and 2022.

We have a duty on Labor Day to think of all those who came before us who fought for our right to a 40-hour work week, the requirement to have restrooms, running water, proper ventilation, and safe workplace conditions. There is still much more to do: re-address child labor laws, fight for family leave and affordable child care, eliminate mandatory overtimes, and revisit the KoL call for Equal Pay for Equal Work.

It’s a dishonor to laborers and labor activists if we stand by and watch the laws fought for by people like Leonora disappear.

Sources:

Altruistic review Jan. 1895, Our Day Publishing Company

Proceedings of the General Assembly of the Knights of Labor of America

Report on condition of woman and child-wage earners in the United States

https://www.americanprogress.org/article/project-2025-would-exploit-child-labor-by-allowing-minors-to-work-in-dangerous-conditions-with-fewer-protections/

Certainly an exceptional woman! Hard to believe that she was allowed access to those factories to document the atrocities. We must stay ever vigilant

The statistic: "According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, 57 children under the age of 16 and 68 teens between the ages of 16-17 died on the job between 2018 and 2022." is horrifying! Whatever happened to modern life, the health and wellness of our future generations!? As a mother of two teens, I am first off, thankful to live in Canada (though we have many problems of our own) and secondly, appalled that the labour laws that so many worked for so long to put into place, are being slowly eroded in America.