Saluting Labor Leader Leonora Kearney Barry

Discrimination kept her from her teaching profession. But then she schooled a nation on how laborers ought to be treated.

Shivering in the upstairs bedroom in Gram’s house, I look out the window. The snow drifts are more than five feet high. The wind has carved monsters with their mouths frozen open. My fingers touch the glass, and it is both with wonder and horror that I realize there is ice on the inside of the bedroom window.

I was only 10, but even then I wondered how anyone could have settled in Northern New York, that vast area along the St. Lawrence River that divides the U.S. and Canada, before there was central heat.

But that was before I met Leonora.

At work, we often fight for resources. But imagine fighting for proper lighting or ventilation. My maternal great-grandmother’s cousin, Leonora Kearney Barry, might be one of the reasons we don’t have to plead with bean counters about such things. And for that, and more, we should be thankful. Despite being a fierce labor activist for children’s and women’s rights, Leonora is virtually anonymous in her role in workplace reform.

Since childhood, I have been intrigued by women who were pioneers in their field. I was thrilled when my aunt told me about Leonora a couple years ago. I Googled to find there wasn’t much and the little information there was, was pretty similar:

Leonora was three when she emigrated to the US from Ireland. Around age 15, her mother died, and her father remarried. She married William Barry, and was forced into the labor market, when he died. Leonora was horrified by what she saw. What started as a means to feed her family, became a mission to reform the world of labor. Later she remarried and became Lake. As Mother Lake, her influence expanded.

That left a lot of gaps for me to puzzle out. Going more slowly, and digging into footnotes, I found an essay Leonora had written in her later years.

I was left, without knowledge of business, without knowledge of work, without knowledge of what the world was, with three fatherless children looking to me for bread.

There are, in this country right now, those who believe women should not work outside the home. But they never bother to address what happens when women obey the social contract - only to have it disappear because death or divorce. I imagined the bitterness and anger Leonora must have felt.

Work in textile factories in the 1800s was grueling, conditions were horrific, and men were lecherous. Massive machines left little room for humans, creating unsafe conditions for anyone with scarves, long hair, or long dresses. Steam-powered spinning and weaving devices created chokingly hot working conditions. And windows were shuttered to keep heat in – so the threads didn’t snap. Working in dimly-lit rooms with lint-filled air amid the deafening roar of looms created high risks of blindness, mouth and lung cancers, and hearing loss. Tiny children were conscripted to squeeze into tight areas to change bobbins on machines that regularly snatched slow-moving fingers.

And the pay was often piece rate – based on the output. Leonora made 11 cents her first day, and 65 cents for the whole week - despite working nearly 70 hours.

Toward the end of the 19th century, a federation called the Knights of Labor (KOL) formed in Philadelphia. Workers from all trades - skilled and unskilled lobbied in solidarity for eight-hour work days, safer and more sanitary conditions, and consistent pay. By 1886, nearly 800,000 members were affiliated with the KOL, including Leonora Barry.

She was president of her local chapter of 1,500 female knitwear workers; then president of District Assembly 65, which represented 52 locals and a total membership of over 9,000; finally, by 1886, Leonora was a national organizer and investigator of the horrific factory conditions for women and children.

Her efforts were ground breaking. Eli Cook, author of The Pricing of Progress: Economic Indicators and the Capitalization of American Life (Harvard University Press, 2017) called Leonora “one of the great - and forgotten - economic thinkers, [whose mission was the need for] equal pay for equal work.”

What motivates a person - a person with tiny mouths to feed no less, to decide to become an activist? And why did she think she would succeed? I needed more context about this woman.

I began my research again - this time starting with her place of birth– Cork.

Honora Marie Kearney in Cork, Ireland

Armed with her presumed name, the year she was born, and the names of her dad, John Kearney, and her mother, Honora, I dug into the Irish database FindMyPast.ie. Hours flew by and I came up empty. One of the frustrations in looking at Irish records is there are numerous ways to spell the same name. English was widely used in and around Dublin, but the southwestern counties spoke Munster Irish, which is a form of what most of us refer to as Gaelic (although the Irish fiercely refer to the language as Irish). Within Munster Irish, there were six dialects. And of course, there was always the pervasive, if not intrusive, English.

Estimating her parents’ wedding to be between 1830 and 1842, I sifted through Irish church records. There were dozens of John Kearneys all over Cork. I went up and down rabbit holes, until finally settling on one baptized in 1815. Now I needed to find his wife. Modern day write-ups referred to her as Honora Granger Brown. But I had no luck. I finally found an Honora “Browne.” Adding the “e” is prevalent in south of Ireland. There was no indication of Granger in her records. The couple was married in Kilmichael, Ireland, in 1838.

Despite having the parents’ information, I struggled to find Leonora’s baptismal record. I knew their daughter was born in 1849. So I started again, this time looking for the mother. No wonder I couldn’t find the baby girl. Born to Honora Browne and John Kearney was baby Honora, baptized on August 15, 1849 in the parish of Kilmichael, with a listed address of Carrigdangan.

In wading through what must have been thousands of church baptismal, marriage, and burial records, I found ‘Honora’ to be a common Irish name. Likely a derivative of the French Saint Honorine, who lived (and was martyred) in the Norman region of France. I have no idea how the baby’s name changed to Leonora.

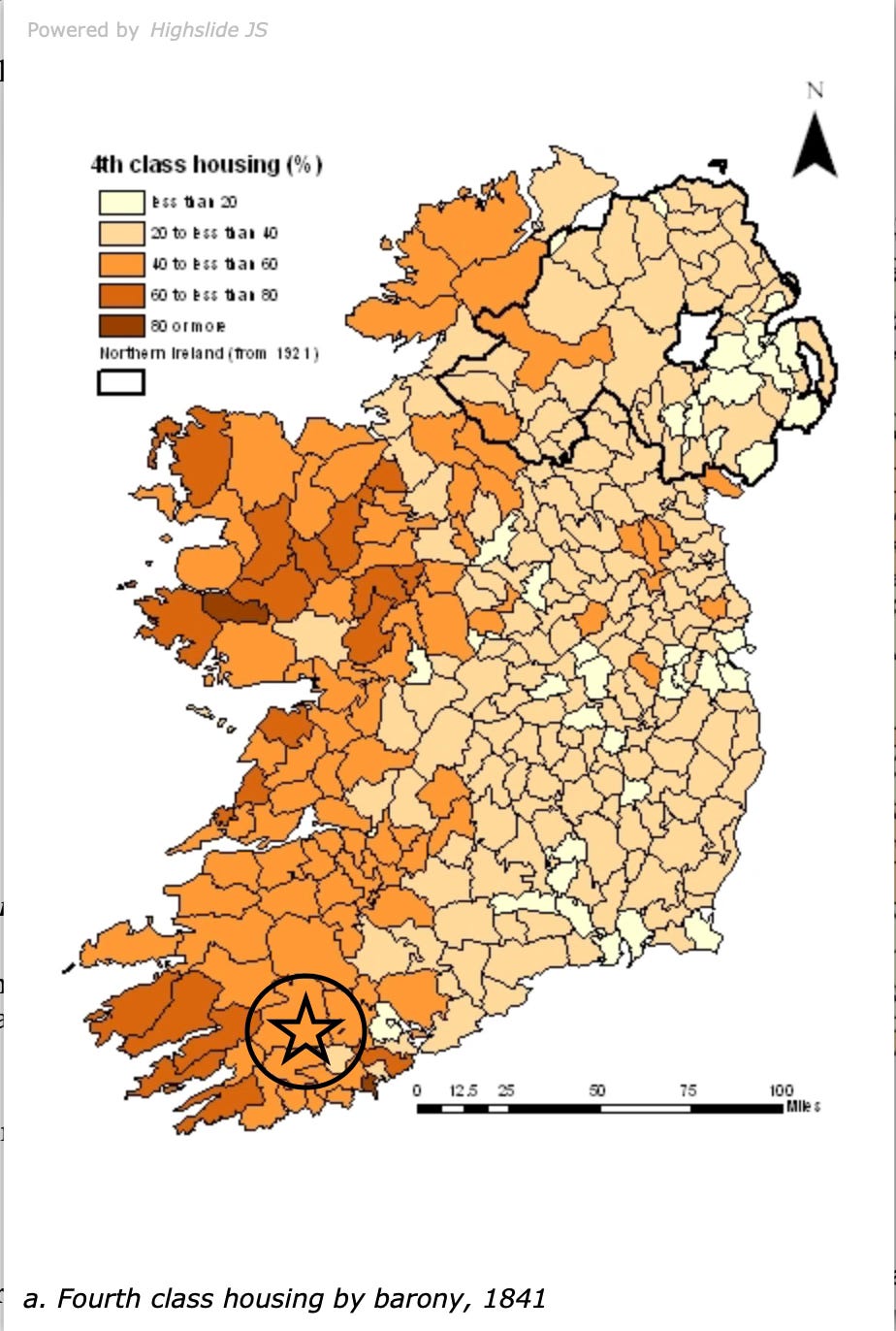

Carrigdangan was in the parish of Kilmichael in the barony of Muskerry West - one of 24 baronies in County Cork. I estimated its location on the map above. It was barely considered a village and was in a rural area and impoverished area. Literacy was considered high - based on their inability to speak English. According to a map in the book Troubled Geographies, in 1841, 40-60% of all homes in the barony of Muskerry West were 4th class housing. Fourth class housing was classified as “mud cabins having only one room.”

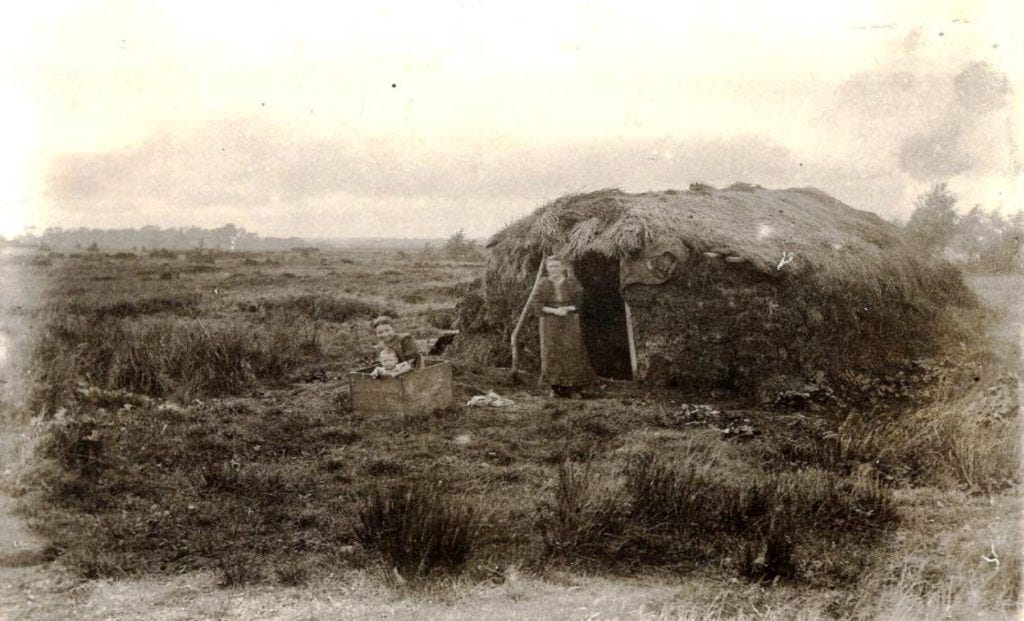

There are no artifacts from this period, as homes just disintegrated and returned to the earth.

Image courtesy of Skibbereen Heritage Center.

During this time in Irish history, most Catholics were forbidden from owning land, following Cromwell’s confiscation of Catholics land in the 1600s. There were exceptions, but for the most part, the land had been given to Barons to own, and the Catholic tenants toiled. Potatoes made up nearly the entire diet of the poorest - any other crops that were farmed were sold by the barons.

When the Great Famine hit in 1845, it further devastated the western part of the county. Landlords wanted their money, and tenants who couldn’t paywere incarcerated in workhouses. “Workhouses” were a 19th century rebrand for poorhouses. The infirm, orphans, elderly, wayward women, and chronically unemployed were housed and “provided for.” The stipulation was that “provided for” meant in a manner that was less than what people outside the workhouse had.

A workhouse opened in Cork in 1840 that could house 2000 people. By 1846, the building was overflowing, people sleeping four to a single bed. Not surprisingly, diseases like small pox flourished. Within the walls of the workhouses or outside, starvation and death was rampant.

Robert Bennet Forbes, commander of USS Jamestown, a relief ship that brought provisions for distribution in Cork, walked the streets and alleys and wrote:

I saw enough in five minutes to horrify me, ‘hovels’ crowded with the sick and dying, without floors, without furniture, and with patches of dirty straw covered with still dirtier shreds and patches of humanity; some called for water to Father Mathew, and others for a dying blessing.

While crops were growing again by the time Leonora was born, it would take years to undo the damage - to the soil, the population, and the economy. By the time Leonora was three, nearly a million Irish were dead. Another two million would make their way to the United States, including the Kearney’s. My understanding was that the Kearney’s spoke English and Irish, and, according to my Aunt Molly, had “some money.”

An 1890 article in Locomotive Fireman’s Magazine reported that Leonora’s mother came from “English ancestry and noble lineage … though suffered impoverishment through the fickleness of fortune.” I haven’t yet found any record confirming that, it is likely she lived near the capital city and had access to its cultural amenities.

The Kearneys in Pierrepont, NY

Around 1842, the Kearney’s left Ireland to move to the United States.

A relative of Leonora’s father Daniel (and the father of my great grandmother) – had emigrated to the United States, and was working on a farm in Pierrepont, New York. Pierrepont is a tiny town located almost dead center in sprawling St. Lawrence County, just 30 miles from the St. Lawrence Seaway that separates the US and Canada, and 30 miles to the Adirondacks in the south.

There are 200 rivers, ponds, and lakes in St. Lawrence County. It is an ideal destination for camping, canoeing, white water rafting, salmon, trout, and bass fishing - and counting the many types of cows that graze the lush countryside. I know the area well because I spent every summer about 10 miles from Pierrepont at my Gram’s - whose mother was a cousin of Leonora’s. The winters, however, are brutal. It wouldn’t just feel like 40 below zero - it was minus 40. Walking outside, I didn’t just see my breath - I heard it. As my breath froze, I could hear the tiny crystals ringing. More than once I wondered how anyone could live there without central heat.

But after the Kearneys saw the horror of people starving to death in Ireland, Pierrepont must have seemed like Eden. And unlike in Ireland, they could own the land.

By the 1860 census, John Kearney reported that the family farm’s value was roughly $1200 - average for a family in Pierrepont. Leonora had some formal education, but her mother Honora supplemented most of it as her father John did not think the investment was worthwhile. Her mother, fluent in seven languages, was the one who taught her the classic arts including poetry and languages.

Honora died when Leonora was 15, and a year later John married a woman name Honor Granger - who was just three years older than his daughter. That explained the confusion of listing Honor Granger as the mother. No doubt because of the image below. Courtesy of the St. Lawrence County Historical Association Quarterly, it shows John’s tombstone - with the second Mrs. Kearney, in St. Patrick’s Cemetery, Colton, NY.

Following her father’s remarriage, Leonora moved out, took a certification course, and became a third grade teacher. She taught for five or six years and then married another Irish Catholic immigrant, William Barry. Marriage was a defining moment for women in those years. As soon as a woman said “I do,” she was forced to quit because of discriminatory “marriage bars.”

It wasn’t just discriminatory gender laws that impacted the Barry’s. Employers discriminated against the Irish (and Roman Catholics specifically), which made employment difficult for her husband. In 1881, her husband succumbed to a lengthy lung ailment, and shortly after, their only daughter died. Widowed with two young boys, including an infant, Leonora took in mending and worked as a seamstress, but the work was sporadic.

She found work in a textile factory. Leonora found the work to not only be arduous but demoralizing. Talking wasn’t allowed; if you were late for work, you were docked pay; joining a union was forbidden; conditions were unsanitary; women were sexually assaulted.

I found an essay Leonora wrote in 1893, The Dignity of Labor in Theory and Practice, that gave me a clue as to how dispiriting experience was. Here’s an excerpt:

Again, labor can not be either noble or dignified when the demand upon the physical and mental energies is so severe that the laborer becomes a drudge, as we find in many cases, where long hours and arduous toil deprive human beings of the necessary time for recreation and recuperation.

Outraged, she joined the Knights of Labor, (KoL), and shortly after became it's national inspector. For four years, Leonora traveled the country observing and interviewing workers. Her husband’s family took one son, while her other son was boarded at a convent school in Philadelphia. I can’t begin to imagine the strain on be her and her children.

I thought about what it must have been like for a 30-something year old widow to travel in the late 19th century. Did she travel first class - which boasted a ladies-only car that segregated her from the leering eyes of men? Or, did she travel in the more affordable second class car which did not offer such an amenity? The jolting trains often caused headaches and nausea. The stations were a meld of rich and poor, men and women, civilized and not so, and all races. Would she walk from there to the factories? or take a stagecoach.? It must have been exhausting and grimy.

Factory foremen were not welcoming, sometimes forbidding her from interviewing workers. Yet, she persisted.

She took meticulous notes on pay ranges, average pay, hours worked and sex of employee across all industries. But she didn’t just chronicle the statistics. She colored the facts with vivid examples of hardship and exploitations. In her report to the General Assembly in 1888, she begged the male laborers to join voices with the women who suffered as “slaves to sin and shame.”

In an excerpt of his book, Author Eli Cook wrote:

By the late 1880s, Barry had become renowned for the statistical reports she compiled for annual general assemblies. With an arresting depiction of the condition of women’s labor in America, Barry’s reports combined statistical data with a strong moral critique of industrial capitalism. Her reports focused on both the laborer’s wages and the employer’s profits, which enabled her to measure the level of exploitation at the American workplace.

“The contractor who employed five operatives made 30 cents per unit, or 1.50 a day,” she noted in one example, “while each worker received only 30 cents for the entire day’s work.” “Men’s vests are contracted out at 10 cents each,” she noted in a second example, “the machine operative receiving 2.5 cents and the finisher 2.5 cents each, making 5 cents a vest for completion.” Since twenty vests constituted a day’s work, Barry calculated, “a contractor who employed five operatives reaped a dollar a day for doing nothing while his victim has 50 cents for eleven and twelve hours of her life’s energies.”

She was the only woman to ever hold a national leadership for the Knights - and the only person documenting conditions. The statistics she gathered helped bring awareness to factory conditions, working hours, and pay, and was acclaimed for her role in bringing changes to the workplace. Unfortunately, she was also prey to harassment by employers and KOL leadership, while some Catholic priests denounced her as a “lady tramp." Finally, in 1890 she quit the movement. The KOL faded, and Barry met and married a printer.

Leonora Marie Kearney from Cork, Ireland, became Barry through marriage. After widowhood and remarriage, she became Lake. And later, as Mother Lake, her influence expanded. In the published references about Leonora Barry, that’s where the story ends. But in my research I am finding there is quite a second act. Over the next 40 years, Barry, now known as Mother Lake, would give more than 500 speeches, head the Catholic Temperance movement and author articles about the laboring with dignity, women’s suffrage, equal pay for equal work (for women of all colors).

Was her dedication to these causes because of her Irish heritage? That’s what I am looking to discover. Other notable activists from Ireland included Cork-natives Mary Harris “Mother” Jones, Hannah Sheehy-Skeffington, Dr. Gertrude Kelly, Margaret Sanger, are but a few.

Were they feminists or survivalists? There is no doubt their position in society - impoverished and with few rights - drove them to make changes.

In the aforementioned essay, The Dignity of Labor in Theory and Practice, Leonora Kearney Barry Lake wrote:

“Writers of ancient and modern times, whether in poetry or prose, in referring to labor, have always quoted it as being "noble, holy and dignified.” … Labor is dignified only when the laborer is self-respecting and respected ….

Alas, how different do we find the practice! The nobility and dignity of labor are lost sight of because those who employ look upon it as only a means whereby they may reach the object of their ambition. It [labor] is considered but a commodity to be bought and sold, and like any other article for which we bargain, bought at the greatest possible profit to the purchaser, while the natural necessities pressing the laborer compel him to sell, though he knows he is selling under actual value.”

At 81, she succumbed to mouth cancer.

What a GREAT great aunt and fascinating story about her life and times. Great description of the working conditions for women and children in the garment industry back then. Family history you can take pride in....union pride!

thanks for writing this! I hope to be in touch: I am currently writing a book of labor women and was looking for Leonora Barry information and was thrilled to find this!