Legacy of New York's North Country

There's a region in way upstate New York, where brutal winters eventually give way to the sweetness of spring. These dramatic seasonal changes shape fierce spirits and unyielding resolve.

“Oh my God, It’s free-eeee-zing there!”

People actually shiver whenever people find out I grew up in Buffalo, emphasis on the “free” – often drawn out to two or even three counts. I don’t know why I have this need to argue with them. Sure it can be cold there, but it’s nothing like the North Country, I’ll say. As if they know anything about the most northern part of New York State.

New York is divided into Upstate and Downstate. When living in Manhattan, we used to joke that everything north of 96th Street was upstate. Generally speaking, Downstate is New York (the City – including the boroughs) and Long Island. The majority of the state’s population – and wealth – are jammed here.

But Upstate, where I am from, has seven distinct regions. I grew up in Western New York, which snuggles up to Lake Erie. My mom was from the largest (land wise) and northernmost region – dramatically called the North Country. (The six and a half hour car ride from our house to Gram’s crossed through two other regions.)

Western New York and the North Country are quite distinct. Mom described the suburban Buffalo-area as all sidewalks. And if the suburbs were sidewalks, the North Country was a patchwork of pastures, barns, and silos, dotted with cows, horses, and cornfields that seemed to go on forever.

We made that drive every year until I was 13. That was the year Gram died. After that, Mom didn’t go up as often. As a kid, I hated that drive as I was always car sick. (Probably because my nose was in a book until I was nauseous). To keep me from reading - or fighting with my younger brother John and sister Chris - my mom had us looking for cows. Along the rolling lush hillsides, a silo appeared, and as we cruised closer, we saw the various herds.

“Look, Holsteins,” Mom said as she leaned out the window, and spied the black and white cows. We pressed our faces to the glass to spot the next herd. “Mooo” we screamed. “Those are Jersey’s,” she affirmed when she saw the brown ones that might have a touch of white. Or, “that’s a Black Angus.”

It was no wonder Mom knew her cattle. Her childhood home was near her Uncle Leo’s dairy farm. A long dirt driveway lined with silver maples led to the house. We entered into a large kitchen. After hugs, we ran out the back door - down a path to grain silos, stalls, where, if we were lucky we might see cows up close, and chicken coops. Leo was a mountain of a man, with lots of brown spots on his arms, hairy knuckles, and a big walking cane. He’d usher my sister Chris and me to the chicken coops so we could collect eggs. We walked past some of the Holsteins at the trough, their giant tails swishing away flies.

Besides dairy cows, chickens and endless corn fields, Uncle Leo had sugar maples. I learned at a young age that what most people in Buffalo put on pancakes was just carmel-colored water versus the “real McCoy” found in the North Country. Mom always left with a year’s supply of maple syrup. I recall Mom telling us how in late winter, as the days began to warm again, the kids would help Uncle Leo tap the maples and hang buckets to collect the sap. Eventually the sap was boiled down to a syrup.

A winter treat was Sugar Snow (or Sugar on Snow). Uncle Leo’s wife Helen and Gram heated the finished syrup until it was runny - and poured it on freshly packed snow. The syrup quickly cooled forming a delicious taffy. We tried to make it once in our Buffalo winter, and just made a mess.

On the drive, bovine spotting kept us busy until we grew tired of mooing and seeing so many cows.

“An Amish Buggy!” Mom said.

That grabbed our attention. Our car was coming down a hill and as we looked over the station wagon we saw the square back of a black buggy being pulled by a horse.

“They shouldn’t be allowed to drive on these roads,” muttered Dad as he drove up behind it.

“Frank! Don’t drive so close.” Mom always thought Dad drove too closely.

“I’m trying to pass.”

“You can’t, it’s a solid yellow line.”

“God Dammit,” Dad said.

My stomach was in a knot as I watched the growing stretch of solid yellow, knowing that Dad was annoyed and Mom was vigilant. Finally, a dotted one. Dad sped up to pass. We gaped at the man in black with a wide-brim hat as he sat with his hands on the reins of his horse and just trudged along.

I preferred driving up to the North Country when it was just Mom, Chris, John, and me. Not only because we didn’t have to deal with the stress of Dad stalking Amish buggies, but because I could sit in the front seat and not feel sick the whole time.

Mom had a tough time leaving the North Country after our visits. She seemed more self assure, more alive when she was there. She loved the small towns, drinking wine, meeting up with old friends, and laughing with some or all of her seven siblings, and walking instead of driving everywhere.

“You see people when you are here,” she said, for about the 9 billionth time. “In suburbia, the garage doors go up, the cars go out, the doors come down. At night they go up again, and the cars are swallowed.”

Cars being swallowed was my favorite part of her litany.

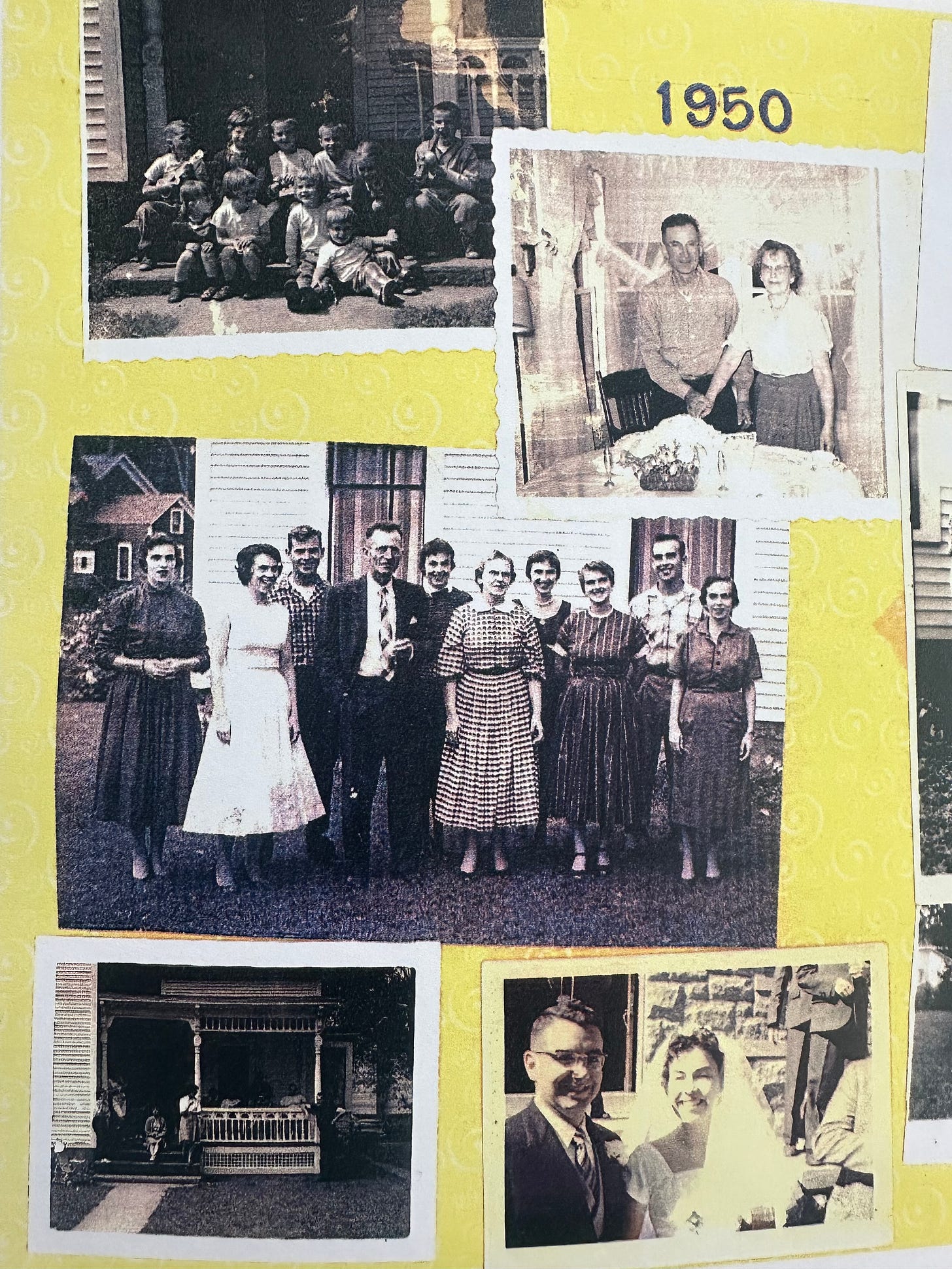

We went to the North Country every summer – staying at Gram’s white clapboard house in Norwood, NY, just a few miles from Uncle Leo’s. We made the rounds to the four of seven siblings that lived nearby, year round. My Aunt Jean & Uncle Jack were teachers so spent the summer up there with their six boys. Once every couple years, Aunt Eileen and Uncle Warren drove up from Long Island with their eight kids piled in a station wagon. Everyone marveled as we screamed goodbye to them; the back of the wagon almost touched the ground. I had another six cousins who lived near us in Buffalo - but I can’t recall them ever being up there with all the rest of us.

I was in the middle of the pack, like the 20th of 40 grandchildren, whose ages spanned almost 30 years. Whomever was in town descended on Gram’s house to take the littlest ones up to Main Street to watch the annual fireman races on the Fourth of July. Volunteer departments from across the North Country competed in different drills: hose, ladder, and bucket brigade competitions. Afterward, we raced to Gram’s yard to stand in line for dogs and burgers. We had our own concession stand as Uncle Joe and Uncle Paul heaped meat on the grills they had hauled over. As we munched, antique fire trucks, floats, and bands passed right past Gram’s. We trailed after them up to the fairgrounds for rides, cotton candy, and later, fireworks.

I only remember going up to the North Country one time in the winter. I was about 11 or 12. That’s the year I learned how cold, cold could be – and that my teacher was wrong about temperatures. I jumped out of bed one morning to see if much snow had fallen overnight. But first I had to scratch the ice off the inside of the window. When it is that cold, it really doesn’t snow.

Downstairs, Dad was sitting in the dining room reading. Mom and Gram were in the adjacent kitchen drinking coffee. “It’s 20 below today,” Gram said, pointing to the large white thermometer outside her kitchen window. “You need to bundle up.”

Twenty below? Twenty degrees below zero – Fahrenheit - and there was no calculating wind chill in those days. My social studies teacher said it never gets that cold in New York State.

It took us longer to get dressed than we spent outside. My face was stinging and I remember hearing the faint sound of tiny bells; my breath was freezing! The snow crunched under our boots as our noses ran. We crunched around for a while, the snot turning into icicles, before we went back inside for hot cocoa. As I drank it, I wondered how anyone could live here before there was heat.

We drove home in a blizzard with white-out conditions. Dad used the red lights of a plow as his guide to staying on the road, while Mom smoked non-stop worried that the truck would stop suddenly and we would all die.

Our visits to the North Country were a bit more sporadic after Gram passed. After her house sold, we alternated staying a couple days with one of my aunts and uncles who had camps on the Raquette River. While at the camps, we spent all day swimming and wandering through woods, before cooking out and eating s’mores at night. Mom didn’t like imposing, so sometimes we stayed in a hotel room.

The last time I drove up there with Mom was in July 1985 for a formal family reunion. It was at Clarkson University in Potsdam. I think a couple cousins were alumni from there. Chris, Mom and I made the trip and stayed in dorms. Picnic tables were covered with food, and a corn field created our perimeter. I can’t recall many other details, although Mom was in her usual happy space with her siblings.

I can still picture her. She was wearing a white blouse and pink golf skirt. Mom’s typically straight hair was permed ‘80s style - short but full of waves. Seated on a lawn chair, she was dragging on a cigarette and laughing with her siblings. Neither my sister or I could put our fingers on it, but there was something fragile about Mom that day, perhaps it was in her laughter, or the way she lingered in conversations. It seemed the glint in her steel grey eyes was fading. Only 52, Mom was the youngest of all the girls, and if I am being honest, always the most put-together and youthful. So it shocked everyone when she was diagnosed with leukemia a few months later, and died a year after that.

About 20 years later, my husband Tim and I and our two sons, and my brother John, along with his youngest went to another reunion. We were at my Uncle Paul’s house in Massena. He had a terrific yard that spilled into the St. Lawrence River. All the older cousins had kids, and even some of their kids were having kids. It was strange being there without Mom. We were family - but neither John nor I felt like we fit in any longer. Three generations posed with their respective nuclear families. It was John and me by a fence post. The five surviving sisters continued to finish each other’s sentences, as if Mom never existed.

That’s not really fair, I know. Life does go on - for them and for us. Without Mom it felt as if our link to the family tree had weakened. Still, Aunt Molly, the eldest and the keeper of our history, remained a steady presence. In the last few years, I’ve had a craving to know more about my mother’s family. I’ve been fortunate enough to create my own unique bond with Molly. At 102, she never left the North Country - save for the four years she went to Buffalo for college. Yet, she has a curiosity about the world around her, and is a font of family lore and history.

Life pulled me away from the North Country, but the stories continue to shape me. I heard whispers of a distant, ancestral relative being honored by the state of New York for her role in worker’s rights - over 100 years earlier. A widow with three small children, Leonora Kearney Barry was forced to work in a textile mill near Amsterdam, NY to survive.

But she didn’t just survive. She was appalled by the conditions of the factory, of the abuse that women and children took in this factory, and took it upon herself to fight for fair pay and better working conditions - for the whole country.

In researching and writing about Leonora, I keep asking myself, where did she get the drive – to not merely survive – but fight? A quote from Leonora in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch around 1901 offers a clue. “My people were pioneers in Northern New York.” 1

Leonora was one of the North Country’s own, shaped by the same brutal winters and enduring hope that marked Mom’s and Aunt Molly’s lives.

Did growing up in the North Country offer an inheritance of resilience? Did one gain —an understanding that after every winter, no matter how harsh, there’s a thaw, and the sap will flow again? Did it offer the promise of sweetness, like Sugar on Snow, and the quiet hope of new beginnings?

I believe it did for Mom, my aunt, and Leonora. The stories of them are woven into my life, fortifying me and reminding me that wherever I go, their strengths go with me.

Notes from Betsy Kepes, writer for St. Lawrence County Historical Association Quarterly.

This was a great piece to read. Thanks for sharing Diane. Your winter story reminds me of the winter descriptions in the Little House books and also of the Thanksgiving Song, "to Grandmother's house we go".

Growing up in North-west Canada, I also find it true that the depths of winter contribute to strong and resilient personalities. Perhaps one feels that if you can survive -40, you can survive anything.

There is something about the change in weather which elicits memories of going to grandma's house up north in me. I enjoyed reading your memories of childhood visits to the North Country. Fierce weather requires developing a fierce spirit.