The Footnote

In my research, William Barry is but a footnote. But I found a footnote doesn’t have to be insignificant. Sometimes it carries its own story.

In time travel stories, heroes are warned not to change the course of history – no matter how tempting. And certainly, a dying 38-year-old man with three small children would be a heart-breaking test of resolve. But if that man too knew the future, he would see that through his passing his widow would find an inner strength to become a leading labor activist. Bound by duty, he would want this to come to pass, and beg you not to intervene.

I’ve spent almost a year canvassing newspaper archives, genealogical databases, and Library of Congress letters to find threads of this labor activist’s life for a book project. “Widow” is how she is often defined, because as Mrs. William E. Barry, Leonora Kearney barely existed.

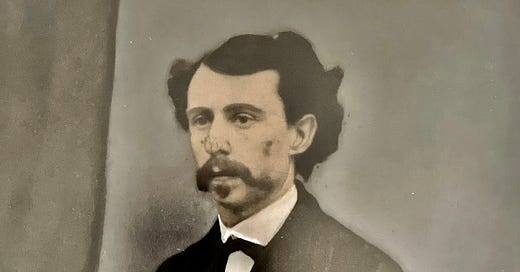

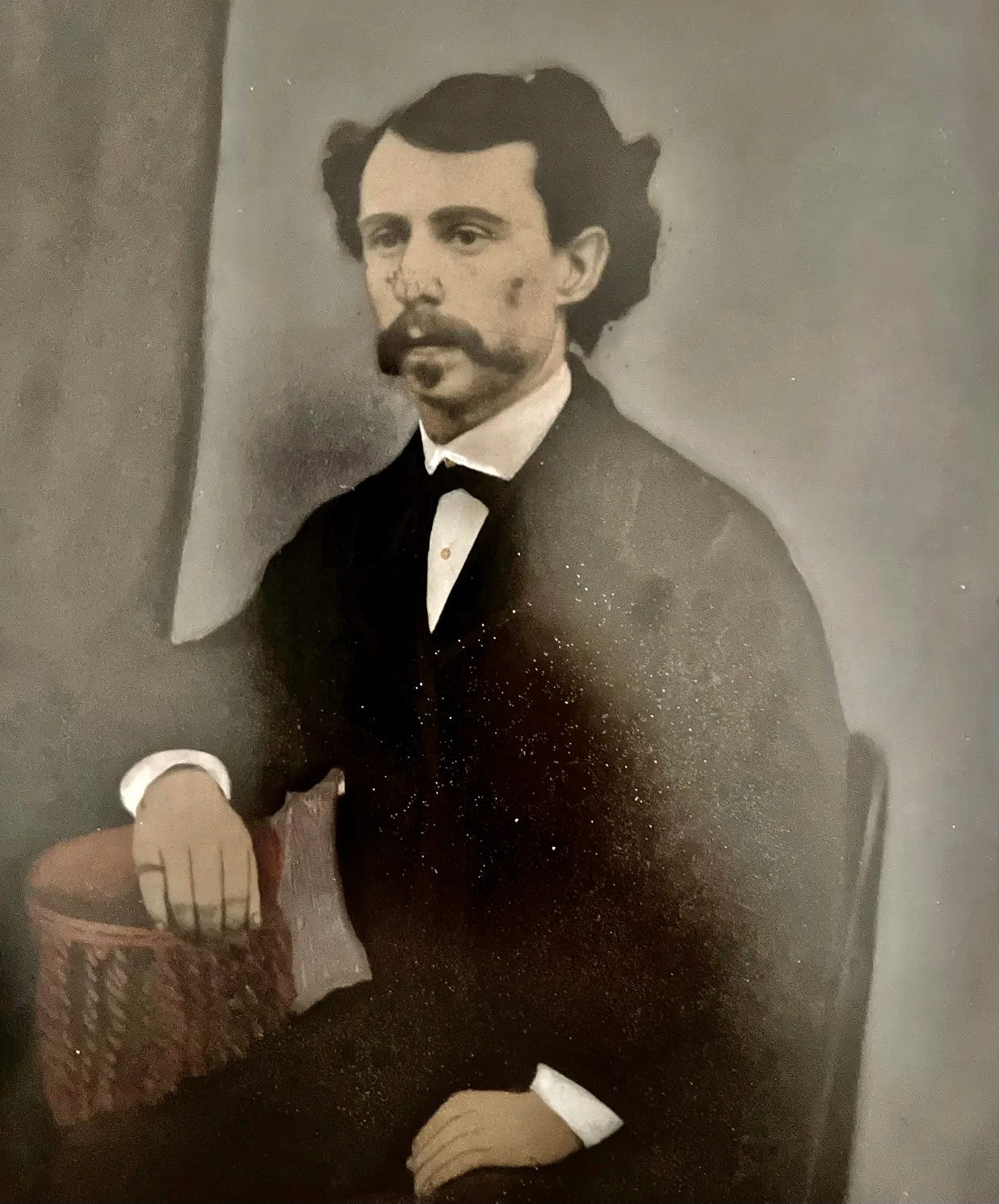

If little was written about Leonora, her husband William E. Barry is pretty much a ghost. I became obsessed with needing to know more about the man who bestowed Leonora his name – and three children – and with his passing, gave her the freedom to become an American legend. Months of research turned up nothing. A fortuitous connection with their great-great-great granddaughter, Julie Whitney, offered a breakthrough.

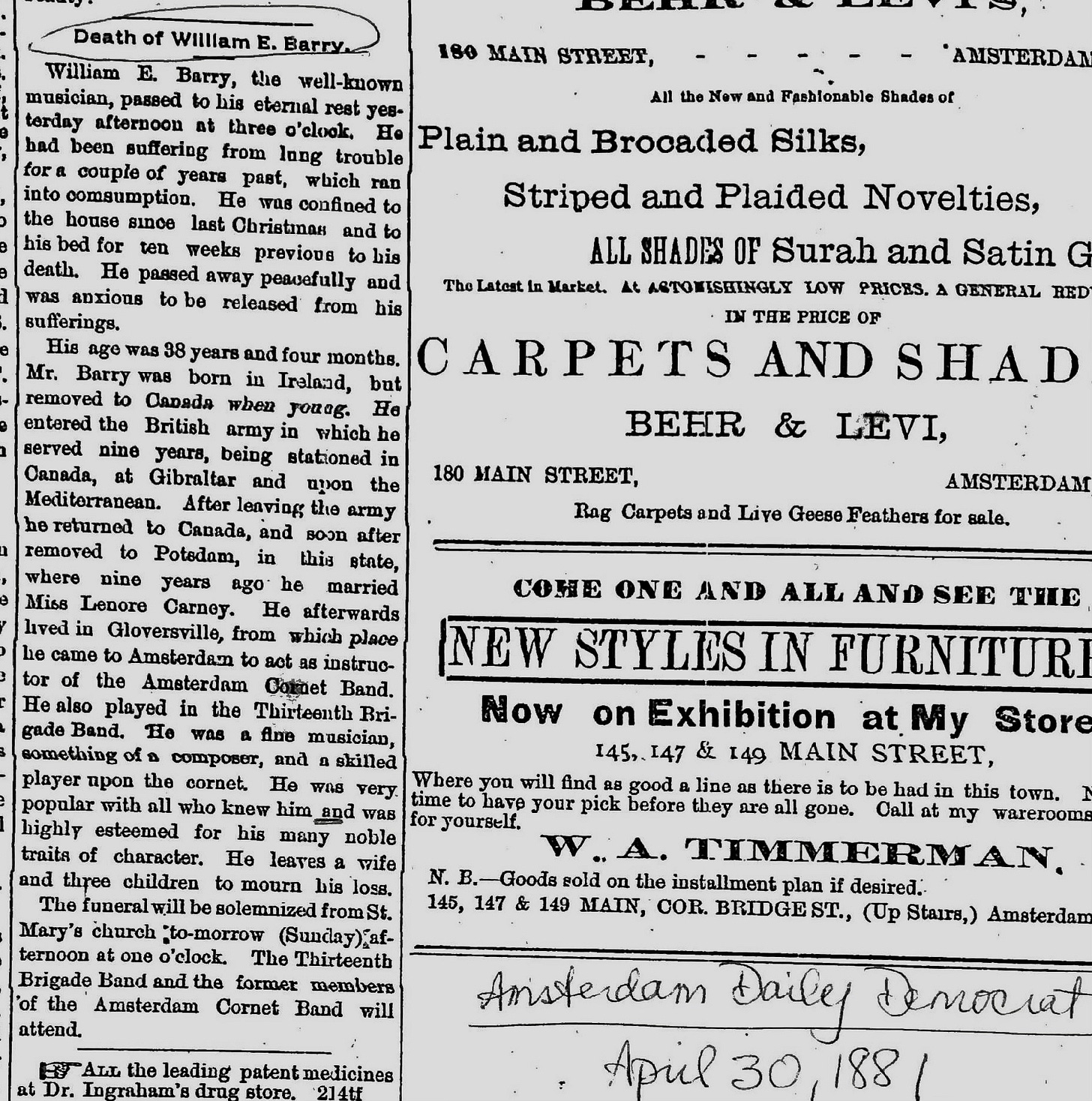

Julie sent me photos of pages from a bible that belonged to Leonora’s grandmother, a picture of William, his obituary, and a photo of his daughter. The obituary was short, but held enough detail to allow me to create a sketch of William. I do make some suppositions - but support them with circumstantial evidence.

William was born in Ireland in January 1843, two years before the Great Famine broke out. ‘Removed’ to Canada as a young boy, he served in the British army for nine years, before being ‘remove’” to Potsdam, New York. From other letters and newspaper accounts, I know William had at least one sister who lived in Potsdam.

The use of ‘removed’ is fascinating.

suggested he might be an orphan - as many were ‘removed’ from Ireland after the famine. With no other information on William’s family, it’s a compelling theory. But ‘removed’ was also used to refer to William’s moving to the United States. The word at the time conferred loss of agency. He was either forcibly removed – or forced to remove himself because of lack of food, money, opportunity.To flesh out more of his life, I considered Irish immigration in general.

Mid-19th Century Canada

In the 1850s, Canada was known as the British North American colonies. Eighteenth century Irish-Protestant immigrants established settlements on cheap farmland around the great lakes of Erie and Ontario. These settlers were militantly ethno-centric, loyal to the crown, and refused to let Catholics reside in their towns. After the Great Famine, desperate Irish Catholics migrants like William, were shunned in what is now known as Ontario. However, they were welcomed in Quebec, Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island. It’s logical to assume young William landed at the port of Quebec, and that he and his (natural or adopted) family settled near the St. Lawrence River along the New York border.

The second part of his obituary offered more clues.

While in Canada, William was in the British Army – stationed in Gibraltar and the Mediterranean. After leaving the army, he moved to Potsdam, and moved to Amsterdam, NY, as a skilled musician and band leader.

So many questions! Why Potsdam? How did he become a skilled musician? To answer the Potsdam part, I looked further to see if there was an intersection between his military service and being a musician. The very name of his band: The Thirteenth Brigade suggested a military connection. I found a clipping in an 1876 newspaper that publicized a concert he played in. Most of the songs were military marches.

Military Music

It’s hard to believe, but mid-19th century entertainment was a vestige of war.

Throughout history, militaries used musical instruments to provide a call to arms, a battle cry, and a means of communicating across the battlefield. Piercing tones conveyed commands, galvanized troops, and created formations. Early European and Muslim instruments were constructed from whatever was plentiful - animal horns, hides, wood, silver, bronze, and copper.

Beyond terrific paintings, the Renaissance era ushered in brass, which was an ideal material for creating new horn shapes with twists and turns of tubing. Brass wouldn’t rust or fall apart in the rain, either. No corrosion meant a more expressive sound could be made by using slides and valves. Of the brass wind instruments, the most agile to maneuver was the cornet - a smaller trumpet that could be mastered with one-hand while on horseback. An important task if you were a mounted musician.

As the instruments evolved, so did the musicians’ skills - as well as their roles within the regiments. When the troops weren’t playing, they became stretcher-bearers to care for the wounded. By the 18th century, the British army had incorporated at least eight musicians within every regiment. The practice caught on across Western Europe and North America. Yes, music was used for signaling and commands. And, as much as it was for the troops, military music generated excitement for the citizenry during ceremonies and parades.

With all the advancements in instruments, with music entrenched in war activities, and with plenty of military activity following the War of 1812, the Civil War, and just making sure that no one was encroaching on any territories, there were plenty of retired military musicians - itching for a chance to continue playing. They formed fraternal organizations - brigades and regiments of skilled musicians. They played concerts as entertainment and in ceremonies for funerals, parades, the inauguration of a new ocean liner or railroad. Anything worthy of fanfare. An 1877 playlist included music by Verdi, biblical sonatas from Johann Kuhnau, operas by Auber, and of course marches by John Philips Sousa.

We know that William Barry was an accomplished cornet player. In an article about Leonora penned by Eugene Debs, a quadrennial presidential candidate on the socialist ticket, he wrote that Barry was a musician and composer “of note and merit.” One can’t be that way without years of commitment. I decided to make the leap that William was indeed a musician in the military.

As to why Potsdam, here’s my theory.

Potsdam, NY

Potsdam is a small town located on the southern side of The St. Lawrence Seaway in St. Lawrence County. It was named after the Prussian (now German) town of Potsdam, because of its rich deposits of sand stone. Following the American Revolution, politicians wanted this northern area of New York fortified against the Canadian loyalists. At the same time, the Governor of New York had a goal to facilitate education. The St. Lawrence Academy was founded to create programs through Normal Schools to teach teachers - including music teachers.

Normal Schools were the predecessor to the State University of New York system (SUNY). In 1861, the Northern New York Musical Association was formed to elevate the “musical taste, and the promotion of a more general cultivation of musical skill, especially in vocal music.” Members, who weren’t paid, performed two concerts a year. It’s likely that these events created interested in tutoring - which the members were eager to do.

It’s possible that the St. Lawrence Academy and the musical association were draws for William. Perhaps he moved to Potsdam in hopes of teaching music at the school - and still being near his Canadian home. It was in Potsdam that William met Leonora. They married in 1871.

He painted houses and worked as a musician - perhaps tutoring and playing in marching bands. With family nearby, I’m certain the couple would have liked to stay in the area. But similar to Canada, discrimination against Catholics was rampant in New York’s North Country. It was still evident 70 years later. My Aunt Molly, a native of the adjacent town of Norwood, NY, received her teaching degree from D’Youville College in 1941. She taught business, which was highly sought out by schools. She told me: “I went to a Catholic college and never would have received a teaching contract in Norwood if I wasn’t a business teacher.”

Leonora and William’s daughter Marion was born in 1873. The toe-head had her father’s eyes and her mother’s smile. The young family decided to leave Potsdam for Central New York – specifically the Mohawk Valley, where patrons of music were located. An abundance of waterways including the Erie Canal and construction of railroads made towns around Amsterdam, NY, a hub for both culture and industry.

William found work as a house painter, and as a musician and composer for military bands. One of the bands was the Gloversville Cornet band. The bands’ benefactor was John Henry Starin, a U.S. House of Representatives member and a wealthy businessman. Starin owned a resort and was the largest individual owner of steamboats, barges, and tugboats in the United States. He used his bands to create fanfare for any reason.

The Mohawk Valley

This must have created quite the lifestyle for the Barrys. Throughout the summer months, weekends and evenings meant performances and picnics in parks, in parades, in ceremonies, and on steamships. Throughout the rest of the year, the band would strike up to play at benefits, ceremonies, even New Year’s Eve. Of course, they played on the inaugural voyage of the steamship The John H. Starin. The voyage lasted three days and ran from New York Harbor to Nantucket, back to Philadelphia before returning to New York.

The Barry’s second child, William (Willie) Standish, was born in February, 1877. That household must have been a joyful one filled with music. As the days grew warmer, and William was again playing concerts in parks, you could imagine Leonora and her children relaxing on a blanket watching William in his military uniform complete with cap and white gloves. The mustachioed William would have been quite handsome. Leonora wrote later that “love’s young dream” had been realized.

William left the Gloversville band to join or possibly even lead the 18-piece Thirteenth Brigade Band in bustling Amsterdam. A “William Barry” is listed in the Amsterdam City directory as residing on Wall Street and being a house painter. The modest houses on Wall Street were near prominent carpet factories, and likely candidates for painting. Leonora could take her little ones to see their daddy play in the parades and concerts that took place throughout the city.

No doubt the Barry household was ecstatic when they learned that William’s band would play along with the esteemed 38-piece Brown’s Band of Boston (considered one of the best bands in the country), for the General Z. C. Priest Steamer Company’s annual excursion to Congress Spring Park in Sarasota Springs. The park, with its mineral spring, was a mecca for anyone with health ailments.

That trip in August of 1879 was a crowning moment for William’s professional career, and what dreams it must have inspired. But he would be retired before the next year’s excursion.

Throughout the 19th century, tuberculosis (TB), also known as consumption, was rampant, particularly in close quarters. Spread through the air, there was no known cure until after 1882.

It’s possible that William picked it up as a youngster on a crowded steamship or in an army barracks, and it remained latent. Latent TB could have been triggered by the lead and copper in the house paints, or by the exertion from playing horn. William started having difficulty breathing toward the end of 1879. Perhaps the excitement of the birth of his third child Charles Joseph in March, 1880, pushed him to move past his ailment. He no doubt was taking elixirs like Mrs. Warren’s Family Syrup to help with the cough.

But unable to take deep breaths made playing impossible. Later stage TB is characterized by tremendous weight loss, difficulty breathing, and coughing up blood. In the 1880s census it was noted that William worked only two-thirds of the year. By February 1881, he was bedridden, and in April, after nearly a two-year battle, William Barry died. No doubt he would have been happy to be spared from watching his eldest child and only daughter Marion Francis die in August of spinal meningitis, likely caused by TB. In her bible, Leonora wrote “Mother’s darlings gone to sleep.”

There is nothing else about William. He lived a life of duty and obligation, that was peppered with a passion for creating joy with music. The tragedy of his death at such a young age is but a pause, though.

His even younger widow was forced to endure the grief of his death – and that of their daughter’s a few months later – by herself. Her two sons were only four and one when she was forced into the labor market to earn a living – with no knowledge of business. Kindly neighbors watched her sons as she entered the workforce as a factory laborer. This suggests that the family had a standing in the community – and that the community was willing to rally around her.

I believe that if fate could have intervened, William would have said no. While he knew impending death would take a toll on Leonora, maybe he knew something else: that she was strong enough to rise. That the same qualities that drew him to her – her conviction, her mind, her fire – would carry her forward. In a few short years, Leonora would become a dominant force across the country to highlight workplace abuses.

William has been a mere footnote to Leonora. It wasn’t he who changed the world – but his absence made space for someone who did. A kind of resurrection, not of him, but of her purpose.

It doesn’t diminish her brilliance to suggest this: Maybe he wasn’t her footnote. Maybe she is his.

More on Leonora Kearney Barry

I’ve been writing about Leonora for a full year now, and It felt important to me to write about William – even though so little was known about him. A special shout out to the Barry’s great, great, great granddaughter Julie Whitney, as well as to Betsy Kepes who has written about Leonora for the St. Lawrence County Historical Association, who introduced Julie and me.

In upcoming newsletters I’ll be looking at some of the other individuals who were in Leonora’s life.

What I Am Reading

In her book, Cowboy Apocalypse, religious scholar Rachel Wagner analyzes the gun epidemic through a lens that looks at how the intertwining of religion and fear create a Gun Messiah; “The good guy with the gun.” With our love of nostalgia, everything old is new again. Cowboys, rugged individualists, gun slingers. Old fears become new ones. And the gun means no further communication is necessary. Through exploration and explanation of this phenomena, Wagner is in hopes that we (finally) learn to listen to one another.

I revert to fantasy this coming week with Sarah Maas’ Tower of Dawn.

A carefully crafted dance in the shadows between fact and supposition. Well done!

This is fascinating, Diane! You found so much information about William’s life in music. Very impressive research. Thank you for adding so much to my knowledge about him!